To my delight and misfortune, I have been making comics since my 2017 Erasmus plus stay at Aarhus University.

I was never very good at drawing, but someone once told me that I was good at making circles, so I stuck with it. When I shared my early comics with my family, I got mixed reactions. In a WhatsApp correspondence, one family member resorted to “wow”, while the other offered their interpretation: “charming illustrations! I suggest not to try to understand the humor. It’s cool that there is a recurring character that repeats throughout. It creates empathy. Even if I do not understand the humor.” 4 years later I was still at it, and sent some more comics to my family WhatsApp group, which by then was mostly in English for my wife’s sake. This time, a family member noted my somewhat improved drawing skills: „Thank you yoav for sharing with us. Your [an expert]. Its beautiful! for me somehow hard to understand”. This family member could not find the word for “expert” in English, so just kept the word and hoped that I would translate this to my wife.

The reason I am sharing this here, beyond disowning my family and losing all hopes for any share in the inheritance, is that I used to think that the problem was either with them, or with me. My 2017 comics were meant for Old Norse scholars, and even then only to those unlucky few who knew my opinions on the sagas and had earlier enjoyed my memes on the topic. My 2021 comics were aimed at a broader audience, so I thought that if my family could not understand them, the fault was either with their understanding, or my drawing skills.

Who Understands Comics? by Neil Cohn has made me realize that the problem was actually not with my family or me. Rather, this gap in communication was due to the fact that I had been reading comic books as a kid, and comic strips as a University student, thus gaining the kinds of visual language literacy needed for consuming and creating within the webcomic medium. My family members, on the other hand, had never read comics beyond Bazooka Joe bubble-gum strips, which meant that they could not enjoy my hilarious comics because they simply did not have the frame of reference with which to understand them.

Cohn’s book sets off in an interesting task: To question the notion that sequential images (comics, airplane safety manuals, IKEA instructions) are intuitive and universal. The answer to this, Cohn shows, is a resounding NO. While this might seem like a minute issue of small importance, it is shown that the Sequential Image Transparency Assumption underlies much research connected with cognition, the mind, and communication. Sequential images are also frequently used as a tool meant to improve interaction in foreign aid situations or when communicating with certain disabled people. Cohn methodologically shows how cultural, age, and mental differences impact one’s understanding of comics and storytelling images at large.

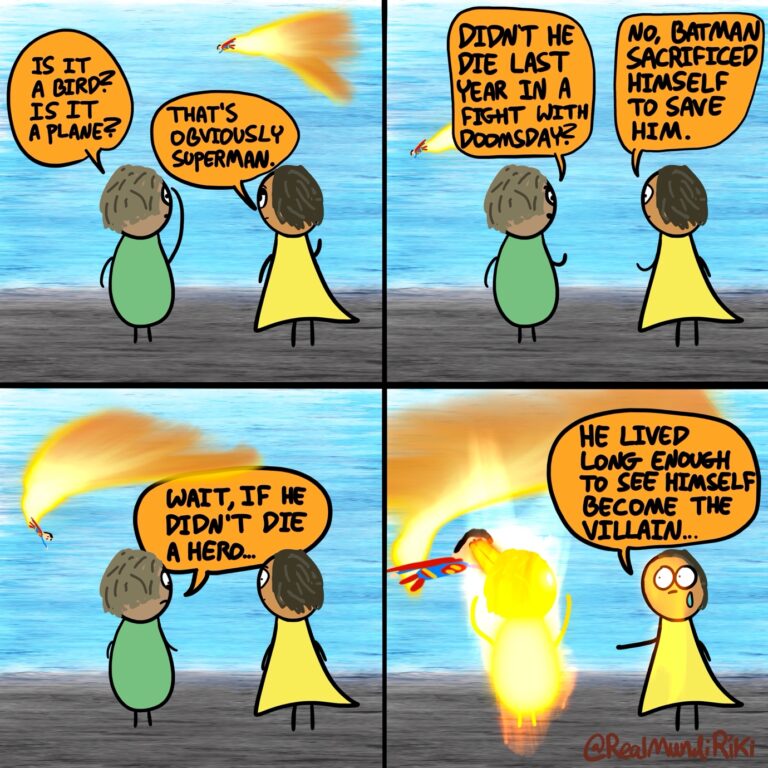

To illustrate the kinds of literacy discussed by Cohn, I can yet again share from my own experience as a person whose mother tongue is Semitic and is thus, as an Old Norse professor of mine frequently states, “written backwards”. When making this comic originally, this seemed totally normal to me:

However, following people’s comments on social media, it became apparent to me that the Roomba in the comic was going the wrong way. Some people even noted not noticing the cleaning robot. I thus corrected the comic:

This confusion clearly stems from my initial experiences of reading comics in translation or in their original Semitic form, going the “wrong way”. What Cohn shows us, though, is that the problem in communication lies not (only) with my limited drawing skills, but rather with my visual language being trained differently from that of most of my comic’s audience.

The book begins by questioning the universality of visual languages. On the face of it, nothing seems better poised for meaning creation than a drawing. A notion that perhaps stems from how we associate drawings with kids’ entertainment. While Cohn does not address this, it is noteworthy that Jason Mittell has illustrated how animation – associated with children to this day, despite adult-oriented shows like Frisky Dingo, Archer, Family Guy and South Park – was first introduced to television in the sitcom The Flintstones, meant for a general adult audience. But animation became a victim of its own success, and after an abundance of ‘duplicates’ (The Jetsons being the most memorable of these) flooded prime time, these were taken off the air, and eventually rebranded and relegated to the ingeniously devised time-slot of Children’s ‘toons. Thus, the association between children and animation is constructed, just as the association between images and easier comprehension is ill-conceived.

Furthermore, the book reveals how knowledge of one visual system does not necessarily imply knowledge of other visual systems, indicating significant differences between Japanese manga and American Superhero comics. Temporal changes also factor into these differences; a deep acquaintance with 60s style superhero comics can cause one to judge harshly the narrative style of a modern-day superhero comic. I could even attest to this myself: I always experienced reading early X-Men comics as agonizing, after being accustomed to the 80s to early noughties comics style(s). Despite not referencing Bourdieu, it is noteworthy how much this study confirms the sociologist’s attestations of taste, code-reading and experience being tied with culture and class.

The book also discusses the influence of age on sequential image literacy, with the astounding observation that rather than teaching children to read through children books’ drawings, children learn to read alongside learning to comprehend images. It then treats case studies of what are referred to as ‘neurodiverse’ individuals, a catch-all phrase that encompasses anyone from people with Autism Spectrum Disorder to Aphasia. While the power of the chapter lies in its exposing the circularity of associating mental difference with lack of visual literacy, it heavily relies on secondary literature and as such is vague on the diagnostic criteria of the cases discussed. What makes a someone qualify as a neurotypical control? How were the control group members selected? Does a person with obsessive compulsive disorder, for example, qualify as neurodiverse or neurotypical when checking for autism visual literacy? While this does not invalidate the important points raised by the book, especially in terms of the communicability of sequential images for disabled people, more attentiveness to other intersectional concerns otherwise addressed in the book would have helped to inspire confidence in the results.

The book closes with a debate comparing still image sequential literacy and film literacy, stressing differences between these mediums of processing information, and finally provides key observations on how to continue this research and approach sequential image meaning making.

As a non-linguist, Who Understands Comics? was more of a challenging read than I bargained for, judging the book by its colorful and attractive cover. In Cohn’s defence, he makes a clear effort to explain all the terms used, and generally builds arguments gradually. It would have been useful to have more illustrative drawings to convey some of the book’s main observations. For a book discussing comics, there were far too few comics to look at. These images were sorely missing, especially when key differences between comic styles were discussed, or kinds of sequential images compared.

Despite my personal limitations, I would venture that this book has changed the way that I look at comics and visual communication at large. At the end of the day Who Understands Comics? is an important reminder that when it comes to communication, comics and other sequential images are a useful alternative method but cannot be resorted to as a catch-all solution. It also raises questions about the cultural bias by which we measure intelligence and cognition. Did I get into gifted class in secondary school because I was very smart? Or was it because my mom finally gave in and started buying me American superhero comics, thus allowing me to better understand sequential meaning making? What matters, I guess, is that my family loves me.

Yoav Tirosh is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions fellow working on medieval trauma at Aarhus University’s department of Scandinavian Studies and Experience Economy. His research focuses on the Icelandic sagas, dealing with topics such as disability, genre, memory, gender and sexuality. He publishes Viking Comics by Yoav Tirosh on most social media platforms. You can follow him on Instagram or elsewhere by searching for @realmundiriki, or at https://au.academia.edu/YoavTirosh

https://www.instagram.com/realmundiriki/

1 thought on “Who Understands Comics? Or: How I learned that I don’t draw bad comics, I just read backwards”