Today it is World Romani Day. Jon Petterson contributes an article about his variety of Swedish Romani.

The first known source of Romani speakers is a document describing a traveling party of a people never seen before arriving Stockholm in 1512. Originally mistaken for being Tartars they came to be called Thatra. Today the term tattare is still in use in Scandinavia. In Sweden it’s considered to be a disparaging term, but in Norway it is used as a self-definition for Romanies.

From the 16th and 17th century, the sources mentioning Romanies with the synonymous terms tartare and ziguenare are very few. In 1637 a royal decree proclaimed that Romanies should settle or leave the country within three months. Some scholars have claimed that the Romanies left Sweden and settled in Finland. Of course quite an unhistorical thesis since Finland was a part of Sweden until 1809.

In 1662 a similar royal decree shows that Romanies lived in Sweden. However, it is quite rare to meet the terms tartare and ziguenare in 17th century documents. Instead, the Romanies were most often called häktmakare (hook and eye-makers), krämare (tradesmen), vandringsfolk (wandering people) and skojare (from Dutch schooier “begger” and schooien “to beg”). Historical documents such as court protocols and church books strongly indicate that it was made a strategy to avoid deportation cases, which were very long and costly processes. Even the church law of 1686 specifically says that children of tartare shall be baptized and tartare in general shall be accepted within the Christian community. This clearly shows that Romanies lived in Sweden at the time.

Why this has any relevance in a text about Romani language is because it is the language of an ethnic group. Today many Romani varieties or dialects, from all over the world, are well researched. However, the Romani spoken and developed in a Scandinavian context since centuries is very poorly researched. The main reason is that speakers of Scandinavian Romani, or ScandoRomani (a term used for Swedish and Norwegian together), have a tradition of keeping the language secret to outsiders. The written sources are, as a natural result of that, very few and the content often quite lean. Another reason is that Scandinavian Romani has developed into a mixed language. The grammar is mostly, but not completely, Scandinavian and the lexicon Romani. Because of that, the varieties of Scandinavia are not always considered to be real languages, as in the language of an ethnic group, but more like slang.

The historical development of Romani in Scandinavia is a natural outcome of the speakers’ historical way of living and speaking Romani. The speakers of today have inherited their language from individuals who can be traced to the 17th century through genealogical studies. Prior to that the numbers of written sources decrease drastically.

In the end of the 17th century, the earliest known sources of people presumably speaking Romani are found. In a protocol from the city court of Falun, a party of Tartare are noted to talk in an incomprehensible language. The language is recognized by the court as the one spoken by ziguenare. By the court it is called rotvälska (rotwelsch), an older Swedish term used for strange and incomprehensive languages in general. Since the persons in Falun were closely related to established Romani speakers, it seems farfetched that their language wasn’t Romani. The earliest example of Romani in Sweden, are some phrases noted by a court clerk in Karlskrona 1709. A woman accused for sorcery gets furious with the court officials and scolds them in Romani. The text shows a Romani spoken with an inflected grammar which is typical for Romani and some Indian languages.

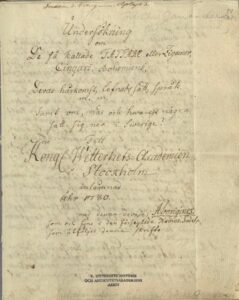

In 1780, Christfried Ganander, a priest in Finland, wrote a prize essay on the Romanies culture and language. His examples of the language shows that inflected grammar is still in use, but the impact from Swedish and Finnish vocabulary is strong.

In 1780, Christfried Ganander, a priest in Finland, wrote a prize essay on the Romanies culture and language. His examples of the language shows that inflected grammar is still in use, but the impact from Swedish and Finnish vocabulary is strong.

The Romani spoken in Sweden and Norway today is not based on the inflected grammatical system as still found in Finland and most Romani varieties. Instead, the grammar is the result of an intertwining between the one in the Scandinavian (Germanic) languages and a Romani (Indic) vocabulary. Mostly only fragments of the original inflected grammar remain. When the development or shift occurred, nobody knows for certain.

In Sweden the focus has historically been on the Romani vocabulary. The source of information on the language was mostly men in prison. In 1730, Samuel Björckman, a scholar at the university of Uppsala, heard about a ziguenare held in custody at Uppsala castle. He visited the imprisoned man, a soldier of the Swedish life regiment — Jakob Helsing. Björckman compared a list of 60 Romani words published in the Netherlands in 1598 with the spoken language of Helsing. According to Björckman, the language was doubtlessly the same. First in the mid 1800s, scattered sentences and phrases in Romani were published in a few books and newspaper articles. The scarce texts clearly show that the language by that time consists of Romani vocabulary but the grammar has shifted into an almost entirely Swedish grammar.

Based on today’s known sources, it is impossible to know when the grammatical shift actually took place. In a wider perspective the Romani speakers of Scandinavia were absolutely not alone to develop similar mixed languages. In several contexts, the Romani lexicon has been kept but the grammatical system been replaced with the one of the majority language. In 2015 the Czech linguist Zuzana Krinková published a comparative study on Romani varieties in Spain. She shows how the inflected Romani spoken on the Iberian peninsula developed into mixed Romani or caló in the 19th century. A similar picture is given in The Dialect of the English Gypsies, written by Bath Smart and Thomas Crofton in the 1870s. They describe how Romani speakers in Britain are at that moment in a phase of shifting the way they speak Romani. The Romani grammar is fastly being replaced by English grammar. “The older forms are quickly dying out and giving way to English forms”.

I the mid 1850s, a Norwegian priest, Eilert Sundt, wrote several publications on Romanies in Norway. The Norwegian and Swedish Romanies consists of more or less the same families still today, suggesting common origins. Sundt suggested that the language spoken with Norwegian grammar and Romani words was a result of intermarriage between two different groups. One that spoke Romani and another that spoke Rotwelsch. According to Sundts thesis the outcome could not be considered to be of ”true Gypsy origin”. In the late 19th century the romantic ideas of authenticity where spread through newspapers and books. In the beginning of the 21st century the pseudoscience of racial biology grew in Sweden. The racial biologists connected purity of the language to the purity of the race or blood. Since the Romani speakers were categorized as a mixed race, their language was automatically seen as a deviation used by asocial elements and criminals. Still today, Scandinavian mixed Romani varieties are sometimes considered to be slang.

The most extensive works on Romani in Scandinavia was carried out by Allan Etzler in Sweden and Ragnvald Iversen in Norway. Etzler worked in the administration of Långholmen prison in Stockholm. There he met inmates of Romani background and collected information from them. In 1944 he became a doctor of history due to his work. Iversen worked within the Norwegian police and published a series of books on secret languages in the 1940’s. One of them is an extensive work on Romani spoken in Norway.

The first work made by a Romani speaker himself was Svensk rommani published in 1977. The author Roger Johansson was a descendant of tartare/ziguenare mentioned in 18th and 19th century sources as Romani speakers. In 1993 a group of Norwegian Romani speakers published their lexicon Tavringens rakkripa – De reisendes språk. Both publications were efforts made by Romani speakers as an attempt to save their threatened language.

The first work made by a Romani speaker himself was Svensk rommani published in 1977. The author Roger Johansson was a descendant of tartare/ziguenare mentioned in 18th and 19th century sources as Romani speakers. In 1993 a group of Norwegian Romani speakers published their lexicon Tavringens rakkripa – De reisendes språk. Both publications were efforts made by Romani speakers as an attempt to save their threatened language.

Today the future of Scandinavian Romani is in jeopardy. The modern life is a great challenge for the actual survival of the language. Not so long ago the speakers lived more closely, often in larger families. Many Romanies lived of incomes from work or trade made far from home. A semi-traveling lifestyle was common. Today traveling with caravans in smaller or larger groups has almost stopped completely. Most Romani speakers do not live as close as they used to do. A result is that situations where Romani is used naturally on a daily basis become more and more rare. Another concern is the vocabulary which isn’t up to date with the modern-day language. Lots of modern words don’t exist in a minority language such as Romani. Nevertheless, there are individuals who still use their language quite frequently. Some have better competence in the language than others, and the ones who know it very well are few. However, in recent years, work to revitalize Swedish Romani has started by organized Romani speakers. As a result of this, the Swedish school board produced a teaching material for children age 9-11 years in 2016. The material has a focus on children without prior language skills. The Swedish State television, SVT, has produced around 50 programs in Swedish Romani over the last five years. The Swedish State radio has produced some 20 productions in the same period. The general desire of the Romanies to save their language and to once again be able speak it in a wider context is substantial. Hopefully future generations of Romani speakers will have a possibility to use the language of their ancestors. The one they brought with them to Scandinavia several hundreds of years ago and kept till today.

Jon Petterson is a Swedish Romani Traveller. He is the president of the Frantzwagner Sällskapet and editor of the periodical Drabbrikan.

Subscription newsletter