We could hear it in the news. Venezuela claims a part of its neighboring country Guyana because it wants to have the oil. Greed. Power. imperialism. The population agrees with the president’s and government’s idea that a piece of Guyana actually belong to them. Hopefully this will not lead to an invasion, a special military operation or a war, or whatever such actions are called these days.

It is not well known that there was a dispute about the border before. A committee that worked on the border dispute came with its judgement in 1899, largely in favor of Britain (at that time it was British Guyana, the country is independent since 1966). The international commission was installed to study all the documentation of the claims, and populations were one part of their research. Creole languages played a key role in this conflict.

Creole languages are new languages that develop in colonial societies. They typically continue the lexicon of the colonial language, but the grammatical system is 80 % renewed. Several Dutch creoles developed in what is now Guyana. Only two have been documented from Guyana: Berbice Creole and Skepi Creole. Otherwise, there are creoles with a lexical base in Arabic, English, French, Malay, Portuguese and Spanish. The lingua franca of Guyana is Creolese, an English-lexifier creole. This is an example of Dutch creole from Guyana:

As you ni passop you sa fall. (Skepi Dutch Creole)

Als je niet oppast val je (Dutch)

”If you do not watch out, you will fall”

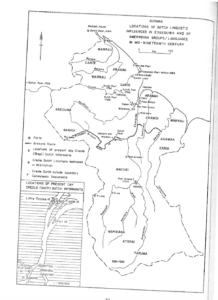

What happened in the Guyanas? One of the first colonial settlements in the New World outside of Brazil and Colombia was the private colony of the Zealandic family Van Peere in what is now British Guyana. It was established in 1627. The Dutch had already traded in the region for several decades by then. Exceptionally, the Berbice colony was not close to the coast but quite far into the interior of the rain forest, along the Berbice River and Wiruni Creek. Apart from this first colony, a number of other Dutch colonies were settled: Essequibo, Demarara and Pomeroon. The Dutch Creole Skepi Dutch developed on the Essequibo plantations. There is, unfortunately, zero documentation of possible creoles of Demarara and Pomeroon.

There is something strange with Dutch colonies and Dutch creoles. There is no overlap between them. In former Dutch colony Suriname (formerly also called Dutch Guyana), five creole languages are spoken, all with English as its lexifier, and one with many Portuguese words, especially verbs. No Dutch creoles developed in Dutch Guyana. In the Dutch Caribbean islands Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, Spanish-Portuguese creoles are spoken. No Dutch creoles. On the Dutch islands of Sint Eustatius, Saba and Sint Maarten, English and English-lexifier creoles are spoken.

Dutch creoles, by contrast, have been documented in the Virgin Islands St Croix, Saint John and Saint Thomas, at the time a Danish colony, and American since 1917. And Dutch creoles were spoken in what is now Guyana, a former British colony. Don’t ask me why there is this lack of overlap.

The Dutch plantations in (what is now) Guyana, were mostly in the interior. The British started to colonize the coastal areas, and in 1814, the Brits annexed the Dutch colonies formally, after having located traders, missionaries and settlers also in the south.

The presence of Creole Dutch speakers in the past was one of the tasks of the arbitration committee. One of the methods they used was going through historical records in order to locate the presence of Dutch speakers. As the Brits had taken over the Dutch areas, those were considered British areas.

Skepi creole of the Essequibo colony was known only from a 200-word list collected by the Guyanese linguist Ian Robertson in the 1970s, a side-product of his dissertation which focused on Berbice creole. His (unpublished) dissertation on Berbice was later superseded by Silvia Kouwenberg’s grammar of 1994. Robertson also conducted excellent research on the historical spread of the creoles. A few decades ago, a sentence was discovered in a letter found in British archives. And in recent years, Bart Jacobs and Mikael Parkvall unearthed more Skepi material from missionary archives, a spectacular find. These finds confirmed that Skepi Creole has developed independently from the other Dutch creoles, and that it was (unlike Berbice Creole) a run-of-the-mill creole, with a typological profile very much like other creoles – if one accepts the robust research results that creole languages are more similar to one another than to non-creoles. Both (in fact all) Dutch creoles are extinct. Skepi Dutch creole died out in the late 20th century, and the last speaker of Berbice Creole passed away as well. Here you can hear the last speaker (even though another speaker was encountered after this as well).

Today, Venezuela claims the Essequibo parts of Guyana, at the least west of the Essequibo river. This time because oil has been discovered there. The population of Venezuela has spoken out in a majority vote that Essequibo should be part of their country rather than Guyana. Will there be a military conflict? Guyana defence forces are on full alert. Brazil already moved troops to the Venezuela border. Venezuela could choose to invade via Brazil.

Will the data on the former Dutch creole again play a role? Probably not. And what about the indigenous languages of interior Venezuela and Guyana?

Unfortunately it has become a habit again to invade neighboring countries the past couple of years.

Peter Bakker is a linguist at Aarhus University. He is a specialist in new languages, including creole languages.

See also this newer contribution:

https://www.lingoblog.dk/en/can-we-linguists-prevent-a-war-how-can-linguistic-research-establish-whether-venezuela-could-have-some-kind-of-right-to-claim-parts-of-guyana/

The records of Rev Thomas Youd found in the records of the Church Missionary Society’s records were first documented and used as part of the data presented in my paper on the Dutch lexicon Creoles in Guiana and the Guyana Venezuela border question published in the mid nineteen eighties in the Bulletin of Latin and American Studies . These data also included samples collected from the only urviving persons who had very passive competence in the language at the time of the interviews on the mid nineteen seventies.

Thank you, Ian Robertson, I mentioned the very important papers in the other blog referred to above.