In the southern part of the Canadian province of Ontario, there are two small Indian reserves on which several hundred Munsee Indians live. Their own language, like so many Native American peoples in North America, has gradually disappeared over the past century, so that by 2023 there is only one Munsee Indian living who grew up with Munsee as mother tongue.

It has been common practice in Canadian schools for much of the last century to ridicule and, if necessary, forcefully stamp out Native American languages from the minds and hearts of Native children. The pain and shame that came with this, eventually led the young Native American parents to raise their own children in English in order to spare them these miserable experiences at school.

In recent decades, the Munsee have come to realize that their own language is not, as the Canadian government and educational institutions have wanted them to believe all along, a backward language, the use of which would leave them with a language deficit in English, and therefore fewer career opportunities in Canadian society.

This realization came late, however, after all the young Munsee parents had started raising their children in English already for several generations, in the sincere belief that they were doing the best thing for their children.

In recent decades, a movement has started on both reserves to save their own language from extinction. Over the past ten years, this movement has gained momentum and the first hopeful results of the Munsee attempts to revive their own language can already be seen.

These developments are the subject of this article. First, though, some information will be provided about the background of the Munsee in Canada and the current situation on their two reserves.

From New Netherland to Canada

The Munsee Indians of southern Ontario have not always lived here. The Munsee originally come from the area of the current metropolis of New York. They are descendants of the Indians who in the early 17th century came into contact with the Dutch, who founded New Amsterdam, the capital of the New Netherlands colony, in their tribal area.

The Dutch eventually lost their colony New Netherland to the British in 1674 and Nieuw Amsterdam was renamed New York. Unfortunately, this change of colonial powers had little positive effect on the local Indian peoples. The colonization of the area by the Europeans only accelerated after the British takeover because numerous emigrants from England made the crossing to the new English colony.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Munsee lost their land to the increasingly numerous white settlers. Part of the Munsee converted to the Moravian (‘Hernhutter’) variant of Christianity in the mid-18th century, propagated by a group called Moravian Brethren. But that too could not turn the tide of steady land loss. Christian Indians also did not seem to have many rights when they were in possession of fertile land on which the settlers had cast a covetous eye.

After several massacres of Munsee Indians by white militias of the newly independent United States, groups of Munsee fled to British-held southern Canada. Here they settled in an area that was not yet so much under pressure from white settlers and where they enjoyed some protection from the British authorities.

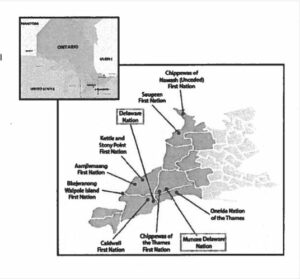

Delaware Nation at Moraviantown

The largest group of Munsee refugees had moved to southern Ontario in 1782 with their Moravian missionary David Zeisberger. After several wanderings, the British colonial authorities assigned them a small reserve on the banks of the Thames River. These Munsee Indians still live here. Their reservation covers an area of approximately 13 km2 and is located in the Chatham-Kent community about 200 kilometers southwest of Toronto, the capital of the province of Ontario and Canada’s largest city. The number of tribal members is about 1100, of which about 450 live on the reserve itself.

It is worth noting that during the Anglo-American War of 1812, the Battle of the Thames took place here, where the great Indian leader Tecumseh was killed fighting the Americans. After the battle, the American troops also burned down the village of the Munsee. However, the Munsee rebuilt their settlement and they have lived there ever since.

Munsee-Delaware Nation

The Munsee-Delaware Nation Reserve is located in southern Ontario about 15 miles west of the town of St. Thomas. It consists of a number of scattered pieces of land within the larger reserve of the Chippewas of the Thames. The Munsee that inhabit this reserve, like the Delaware Nation of Moraviantown, have also lived in this area since the late 18th century.

This group of Munsee refugees from the US was initially assigned a reserve area that they had to share with a group of Chippewa Indians who already lived there. It was not until 1967 that the Munsee part of the reserve was recognized as a separate reserve for the Munsee by the Canadian authorities.

The Munsee-Delaware Nation reservation has an area of approximately 11 km2. The tribe has about 650 members, of which about 170 live on the reserve. The Delaware Nation at Moraviantown reserve is located about 30 miles southwest of that of the Munsee-Delaware Nation.

Five to twelve

At the end of the last century, journalist Steve Wick visited the reserve of the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown. He was in the process of writing a number of articles on the history of Long Island in New York State. Part of this was also about the Indigenous peoples who used to live on the island when the first Europeans settled there.

Munsee Indians inhabited the western part of Long Island, neighboring Staten Island and the adjacent mainland, when explorer Henry Hudson surveyed the area. No descendants of them lived on Long Island anymore at the time that Wick was doing his researches.

Small remnants of the Indian peoples living in the middle and eastern parts of Long Island at the time of Hudson’s visit, such as the Poospatuck (Unkechaug), Shinnecock and Montauk did survive Long Island. However, their language, like most of their traditional culture, had been lost in the process of adjustment to white society.

On the reserve of the Delaware Nation, Wick found what he called “ghosts of history”: a small number of older Munsee Indians, who still spoke their native language fluently. They were descendants of the Indians of western Long Island and the surrounding area, who had been pushed further west by white settlers during the 17th and 18th centuries and who had settled in southern Ontario in the late 18th century. There were about 8 to 10 of them. The youngest Munsee speaker was Dianne Snake, then 59 years old, the wife of Philip Snake, the Chief of the reserve.

Linguists who studied the Munsee language expressed the expectation that it would not be long before the Munsee language would become extinct. The last speakers of the Munsee also shared this fear. Dianne Snake had not resigned passively to this fear and had already started teaching Munsee at the reserve’s elementary school in the 1970s. In the few hours a week that were available to her there, however, she did not get much further than teaching a basic knowledge of the Munsee language to the children. Moreover, there was no follow-up at home, because the parents no longer spoke the language and the Munsee language was not given any attention at secondary schools. As a result, over time, most of Snake’s students forgot what they had learned from her in elementary school.

However, not everyone left it at that. Some younger tribal members had realized that they had to do something to save their own language. One of them was Bruce Stonefish.

Munsee language initiatives on the reserve of the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown

Bruce Stonefish was born in 1972 to Barry Stonefish and Myrna Aikins. His mother descended from a traditional Munsee family where a number of Munsee traditions were kept alive, which they also wanted to pass on to their children. Bruce’s father had no affinity with the traditions of his people. According to him, they were of no use if you wanted to get ahead in Canadian society.

The Moraviantown reserve at that time was a place of poverty, alcoholism and high unemployment. It was difficult then to be proud of being a Munsee Indian and to see the old Munsee traditions as something of value. Bruce Stonefish’s father was often unemployed and he was also an alcoholic with a short fuse.

At first, it seemed that Bruce would follow the path of his father. He started drinking as a teenager and attempted suicide at the age of nineteen, shortly after his mother fled the house to a home for battered women.

However, this suicide attempt turned out to be a turning point in his life. Stonefish came into contact with alcoholism counselor Jim Tobias, pulled himself together with his help, and stopped listening to his similarly culturally uprooted and often socially derailed peers.

Jim Tobias was a veteran of the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee. Working as an alcoholism counselor, he drew on Native American traditions to help troubled tribal youth find a way out of the alcohol trap. Stonefish helped Jim Tobias build the first sweat lodge on the reserve since World War I. At that time, the young men of the reserve participated in a sweat lodge ceremony before being shipped to the front in Europe.

As a child, Stonefish had also taken language lessons from Dianne Snake at Munsee Elementary School, but he had not remembered much of it. When he heard that Snake was also running a Munsee language course for older students, he jumped at the opportunity to learn more about his own language and culture. He also enrolled in the Native Studies Program at nearby Trent University. He wanted to make a significant contribution to improving the lot of his people and their culture.

Stonefish received his master’s degree from the University of Trent and then went on to secure a two-year fellowship at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

However, Bruce Stonefish was already married and had 3 young children. His decision to spend a large part of two years as a student in another country, the USA, was therefore not without a struggle. In the end, his great desire to use his scholarship to fight against the disappearance of the language and culture of his people won out. In addition, he had found to his chagrin that his two oldest children, then 9-year-old Kyle and 6-year-old Jesse, were not at all enthusiastic about learning Munsee. They didn’t understand why they had to learn these difficult things when everyone around them only spoke English. Moreover, their white mother had no talent for learning languages and therefore was not willing to learn Munsee. With more knowledge, Stonefish hoped that his efforts to save the Munsee language would be more successful and that he would be able to reach out to more tribesmen.

After his return from the USA, Stonefish, together with tribal member Glen Jacobs, organized several Munsee language camps since 2005, in which they gave the Munsee youth and other interested people more knowledge of the Munsee language. Also in 2006, Stonefish and Jacobs produced a number of Munsee Language CDs and instruction booklets to promote learning the Munsee language.

At the same time, Stonefish became a member of the Lambton Kent District School Board, that encompasses the schools that the reserve’s youth attend. A group of parents from the reserve approached the school board with a request to teach the Munsee language at the school just like French, Canada’s second official language, is taught at the school. Stonefish helped make this initiative a reality and his fellow language activist Glen Jacobs, who had worked as a Native Education Worker for many years, took on the task of providing the lessons.

In the years that followed, little information can be found about Stonefish’s activities in preserving the Munsee language. Apparently, the hard work to preserve the Munsee language had taken its toll, and had tempered his activity level in that area. However, he never completely let go of this work.

A 2022 University of Toronto Magazine article reports that he was working with linguists at that university to develop an online computer program to facilitate learning the Munsee language.

However, the article accompanies a photograph of Bruce Stonefish, which shows him as a prematurely aged man with poor health. Shortly after the publication of this article in Toronto University Magazine, Stonefish died unexpectedly on May 23, 2022. He was only 50 years old.

The death of Bruce Stonefish, however, did not mean the end of efforts to save the Munsee language on the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown reserve. Already around 2010, a group of five young Munsee had apprenticed with Dianne Snake to learn their own language so that they could later pass it on to the Munsee youth. When, after almost three years of taking lessons from Snake a few times a week, they felt they had not yet learned enough to achieve this goal, they even took a year off from their jobs to be able to study with Snake full-time.

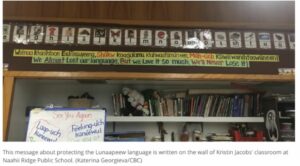

Two of this group of five apprentices of Dianne Snake are primary school teachers, Kristin Jacobs and Angela Noah. They pass on what they have learned from Dianne Snake of the Munsee language to the students at Naahi Ridge Elementary School and Ridgefield District High School. Jacobs teaches Grades 1 to 8 students and Noah teaches Grades 9 to 12 students. Contrary to what was often the case in earlier years, the students are well motivated to learn the Munsee language.

For example, Kara Cornelius from Grade 4 stated “I don’t want to lose our language. We hardly don’t have any speakers left and my grandmother’s mother spoke it and my cousin is now speaking it. So I want to learn the language too.”

The tribal council actively supports the efforts of the two language teachers. Initiatives are also being developed to teach adult tribal members the language through immersion methods, so that they can pass the language on to children. This approach has proven to be more effective than regular language lessons.

Munsee Delaware Nation initiatives to save the Munsee language

Ian McCallum is a tribal member of the Munsee Delaware Nation, which, like the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown, has a reserve in southern Ontario. His father is an English immigrant; his mother is Munsee. As a child, he heard his maternal great-grandfather and grandmother speak Munsee, but pressures at school to learn English and French (Canada’s second official language) prevented him from learning Munsee as well.

McCallum, who is now (2023) 49 years old, as a young adult regretted failing to learn Munsee and began learning his own language after all. However, on his own reserve there was no one left who could teach him that. The last tribal member who could still speak the Munsee language fluently had already died there in 1990. McCallum came into contact with Dianne Snake of the nearby Delaware Nation at Moraviantown Reserve in 1996 through friends. She was one of the very few speakers of the Munsee language there and it turned out she also taught it.

At the time, Snake worked in the tribe’s band office and taught McCallum Munsee during her lunch breaks. McCallum was a diligent and tenacious student. In addition to oral lessons, Snake gave him books in the Munsee language, which McCallum studied intensively. It started with simple fairy tales written in the Munsee language and soon progressed to much more difficult works. McCallum proved to have a talent for language learning and eventually managed to reach the intermediate speaker level for the Munsee language.

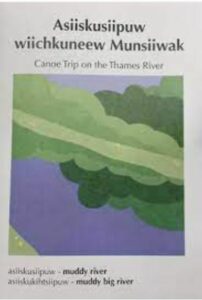

Meanwhile, McCallum had also completed university studies and was working as an elementary school teacher. In his spare time he devoted himself in all kinds of ways to reviving Munsee as a spoken language. In recent years he has written a number of books in the Munsee language for use in teaching the Munsee language and he has also developed computer programs for learning the language. At school, the children of the Munsee Delaware Nation reservation also receive lessons in their own language. Meetings are organized on weekends that are also intended for adults. There are Munsee cultural weekends in which an important place is also reserved for the Munsee language. McCallum is also active on social media such as Twitter, through which he reaches tribesmen who live scattered outside the reserve with his Munsee language lessons.

McCallum does much of his Munsee language work in collaboration with Karen Mosko, another tribal member of the Munsee-Delaware Nation. Their collaboration dates back to the time when Mosko was still training as a teacher, with the aim of being qualified to teach the Munsee language at school.

Mosko’s passion for the Munsee language was awakened when she took a lesson with her mother as a teenager, in which the teacher told them that 200 years ago, all Munsee spoke their own language and maybe a dozen or so also spoke English. That the situation was now completely reversed: that every Munsee now spoke English and there were at most 10 Munsee who could still speak their own language and that they all lived on the other Munsee reserve, that of Moraviantown. From that moment on, Mosko felt it was her responsibility to change that situation.

Both McCallum and Mosko see the lack of sufficient language resources as a handicap in their work to revive the Munsee language, but do not see it as an insurmountable handicap. It makes our job more difficult, but not impossible, is their reasoning.

In addition to his work as an elementary school teacher, McCallum has also become a student himself for several years now. He enrolled at the University of Toronto as a Ph.D. Student with a focus on language revitalization, so that with this knowledge he can better perform his task in keeping the Munsee language alive.

Finally

Discussed above are a number of native language rescue initiatives taking place on two small Munsee reserves in the Canadian province of Ontario. Munsee tribal members do their best here with relatively few resources to save their almost extinct tribal language from final disappearance.

The results so far are modest but encouraging: On the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown reserve, in addition to native speaker Dianne Snake, there are now about 10 to 15 intermediate-level second language speakers of the Munsee language and dozens of tribal members with a still limited knowledge of their own language. On the Munsee Delaware Nation reserve, there are currently two intermediate speakers and several dozen tribal members with limited knowledge of the language. In addition to Munsee language lessons, they are also working on developing ‘immersion’ methods to pass on the Munsee language to very young children.

These language initiatives of the Munsee seem to me to be more than worthy of receiving moral and financial support through the Kiva Language Fund, a Dutch initiative to support language revival initiatives with small grants. The fact that the Munsee are descendants of Indians from the old Dutch colony New Netherland gives this all an extra dimension. It is also a bit of a debt of honor for the Netherlands, because in the past the Munsee were often treated far from fair by the settlers of New Netherland.

At this time, the volunteers behind the Kiva Language Fund are reviewing how we can best support the Munsee in their efforts to save their language. So here we recommend the Language Fund, which can always use your contributions.

Frans L. Wojciechowski (1951) is a retired clinical psychologist (PhD 1984) and still active as cultural anthropologist-ethnohistorian (PhD 1992). His main research interest focuses on eastern Algonquian ethnohistory.

Further reading

Both, Michelle (2022). How a canoe trip on the Thames is reviving an endangered language. CBC (Radio Canada) Podcast, posted July 3, 2022.

Chambers, Steve (2002). The vanishing voice of the Lenape. Star Ledger (Cambridge, Mass.), November 17, 2002.

German, Leah (2012). Last speakers of Canadian Native languages pass on their oral traditions. Beyond Words- Canada’s Official Languages Newsletter, November 10, 2012.

Georgieva, Katerina (2020). How a Ridgetown teacher is part of the fight to preserve the Lunaapeew language. CBC (Radio Canada) Podcast posted January 2, 2020.

Johnson, Rhiannon (2019). Keeping the Lunaape language alive in Munsee-Delaware Nation. CBC (Radio Canada) Podcast, posted December 20, 2019.

Logan McCallum, Jane & Ian McCallum (2020). Indigenous Language Education and online video conference: Initial reflections. Shekon Neechie. An Indigenous History Site. Article posted May 22, 2020.

Longman, Nickita (2022). A lifeline for an endangered language. U of T linguists have partnered with an Indigenous community member to bring the Munsee dialect back from the brink of extinction. University of Toronto Magazine, 2022, vol. 49, no.2, pp. 60-61.

McDowell, Adam (2009). More than words: Can Canada’s dying languages be saved? National Post, January 21, 2009.

McCallum, Ian (2019). Ehahkiiheet Niipaahum recognized in Munsee Delaware Nation. Anishinabek News. The Voice of the Anishinabek Nation, May 27, 2019.

Rivers, Heather (2019). Teacher uses social media programs to revive Munsee language. The Whig Standard (Kingston, Ontario), August 6, 2019.

Wick, Steve (1999). Keepers of a lost culture. A dying language once heard on Long Island is spoken by a few on a Canadian reserve. Newsday. Long Island Our Story. http//www.lihistory.com/2/hs208a.htm.

Koolamalsi,just wanted to know if there is a translation for the the Word

Canarsee,when I was growing up in Brooklyn,my grandfather told me we are from that tribe,but I see all of the tribe left,my question is ,people called it the fence in area,but that word is

Meenaxk.

To Perry Reid

Canarsee —people called it the ‘fence[d-]in area’, but that word is méenaxk. Answer: No, méenaxk means merely ‘fence’. O’Meara does not show “enclosure” in his dictionary. Wm. Bright 2004 has the following: “CANARSIE (N.Y., Kings Co.) \kə när’ sē\. The Munsee Delaware (Algonquian) name has been variously translated as ‘long small grasses’ (Ruttenber 1906) and ‘fenced place’ (Tooker 1911; cf. Grumet 1981).” This is a good source. However, the Internet combined shows the following: The “Canarsee” are shown settled where Brooklyn is today. The Canarsee (also Canarse and Canarsie) has an etymology that is in dispute, but some scholars of Native American tongues say it means ‘fenced land’ or ‘fenced place’.

F. W. Hodge 1907, p. 199, provides the following variants: Canaresse 1656, Canarise 1656, Canarisse 1663, Canarse 1829, Canarsees 1829, Canarsie 1666, Cannarse 1650, Canorise 1656, Conarise 1666, Conarsie 1666, with no translation.

And last is W. W. Tooker 1911 (1975), pp. 31-33: [Not supplied here because of its being an image that can’t be downloaded. Ask me at cmasthay AT juno.com to send it.]