This day in 1987, 36 years ago, the last speaker of Virgin Islands Dutch Creole – Mrs. Alice Stevens – passed away. And with her the language. This post is about the life and death of Alice Stevens and her native language, Dutch Creole.

Dutch Creole was spoken on the three Caribbean Virgin Islands of St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix for nearly three centuries. It existed from around 1700 until 1987, when its last speaker passed away. Alice Stevens was born in 1899 on the island of St. John. Dutch Creole likely originated on St. Thomas around 1700. Thus, she was born when the language was already approaching 200 years of age – a significant span in the life of a human but a relatively short one in the life of most languages. Nevertheless, Dutch Creole was a ‘young’ language, and, in a sense, it died as both a ‘young’ and an ‘old’ language, referred to as di hou creol ’the old Creole’ by the time Stevens was learning it.

Our native languages are older: Danish (KFB) is a continuation of Old Nordic, and a distinct Danish language had developed around the year 800, and Dutch (PB) developed around the same time from a West Germanic ancestor. Both languages (and English as well) go back to the same ancestral language, Germanic. And the Germanic languages form a branch of Indo-European, a language family whose history goes back some 6,000 to 10,000 years and which first began to spread from the region not far from the Black Sea. The development from this ancestral language called Indo-European to Danish and Dutch took many millennia.

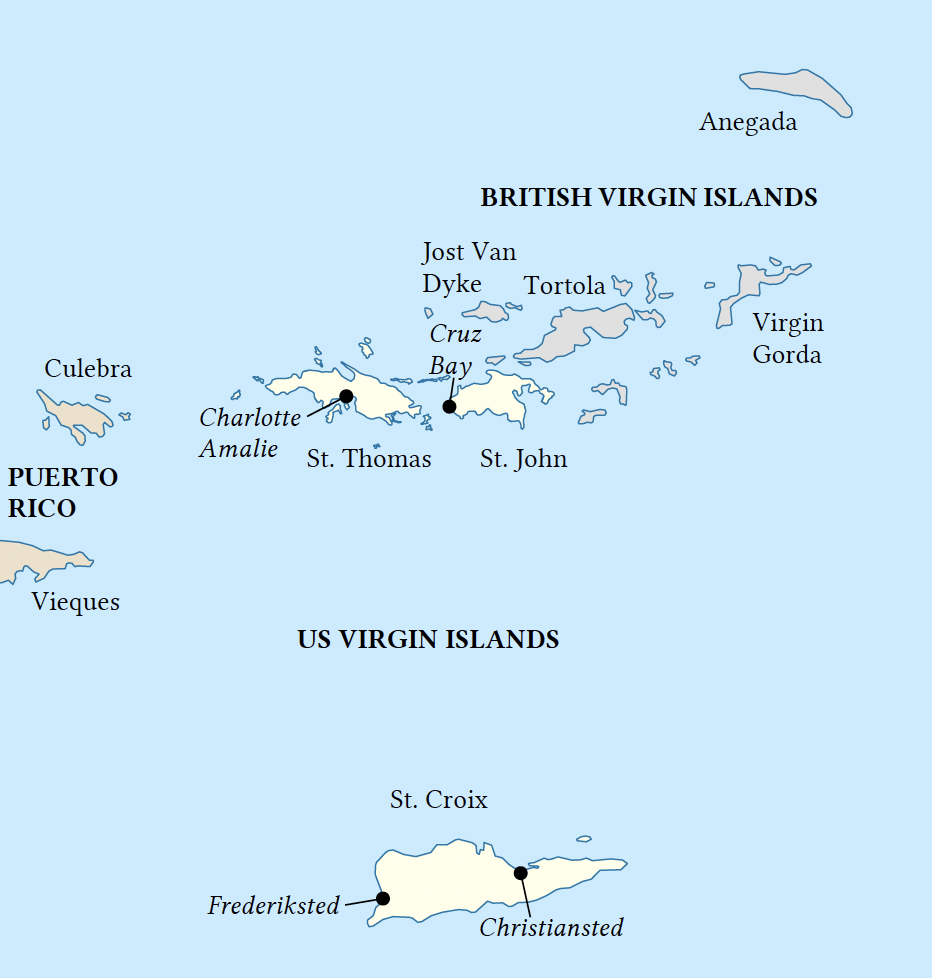

Dutch Creole, in contrast, was what is known as a contact language – a language whose existence is the result of contact between speakers of two or more already existing, older languages. More specifically, it was a type of contact language known as a creole. Creoles are new languages, which emerged more or less suddenly. In the Caribbean, slavery forced humans to innovate new common languages, under adverse social conditions. The date of origin and the place of birth of Dutch Creole are still matters of some debate, but the available evidence suggests that it arose toward the end of the 17th century, probably on St. Thomas, from where it was taken to St. John and St. Croix. These three islands constitute the present-day US Virgin Islands. In the colonial period, the group was a colonial possession of Denmark, known as the Danish West Indies. Slavery ended in the Danish West Indies in 1848. By that time, Dutch Creole had been spoken for roughly 150 years.

Creoles typically continue the vocabulary of a colonial language, but a new grammatical system was developed from the ground up by the people who created the language, often enslaved people on plantations. Alice Stevens’ language had most of its words from Dutch. It also had some words from Danish, but surprisingly few, maybe a few dozens. There were also words from African languages, but not many either. A few dozen words from Bantu languages (Angola) and Kwa languages (mostly Ghana) have been identified. Moreover, there were a number of common loans from Papiamentu, an Ibero-Romance creole of the Netherlands Antilles. Finally, in the 19th and especially the 20th century, the influence from English and local English Creole increased. Yet, it was not a mixed language (another type of contact language), and there were much fewer loans than in Danish, Dutch, or English.

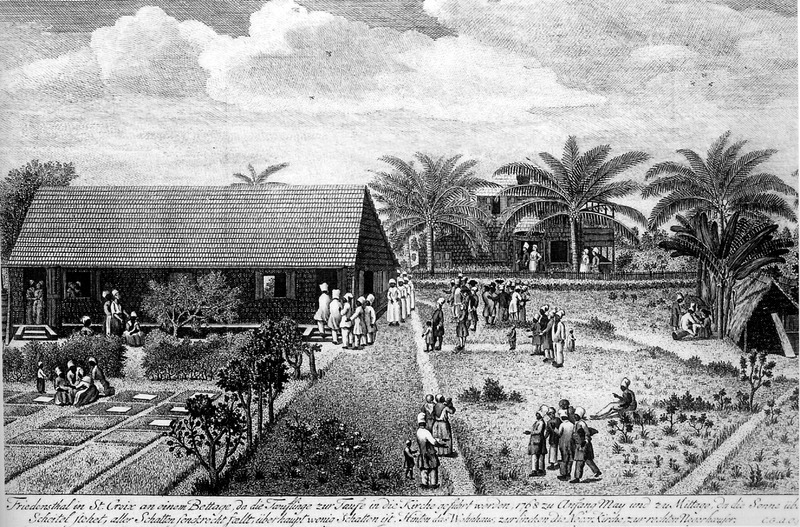

Alice Stevens was born on St. John, the smallest of the (at the time) Danish West Indies. She was bilingual in Dutch Creole and local English Creole. Robin Sabino, a now retired linguist who worked with Mrs. Stevens, remembers: “Mrs. Stevens told me that she was raised by her maternal grandparents from the age of nine months and that she learned to speak her two languages simultaneously.” Learning multiple languages was common in the islands. In the colonial period, Dutch Creole was used by missionaries for Christianizing the enslaved. One of their historians, the German missionary C.G.A. Oldendorp, encountered a very multilingual situation in the islands when visiting in the 1760s. Four European languages were spoken widely (Dutch, Danish, German, English), two creole languages (Dutch Creole, English Creole), and at least 25 different African languages, often mutually unintelligible. The role of Dutch Creole as a lingua franca was special: It was spoken not only by people of African-Caribbean origin, but also by many Europeans on the islands.

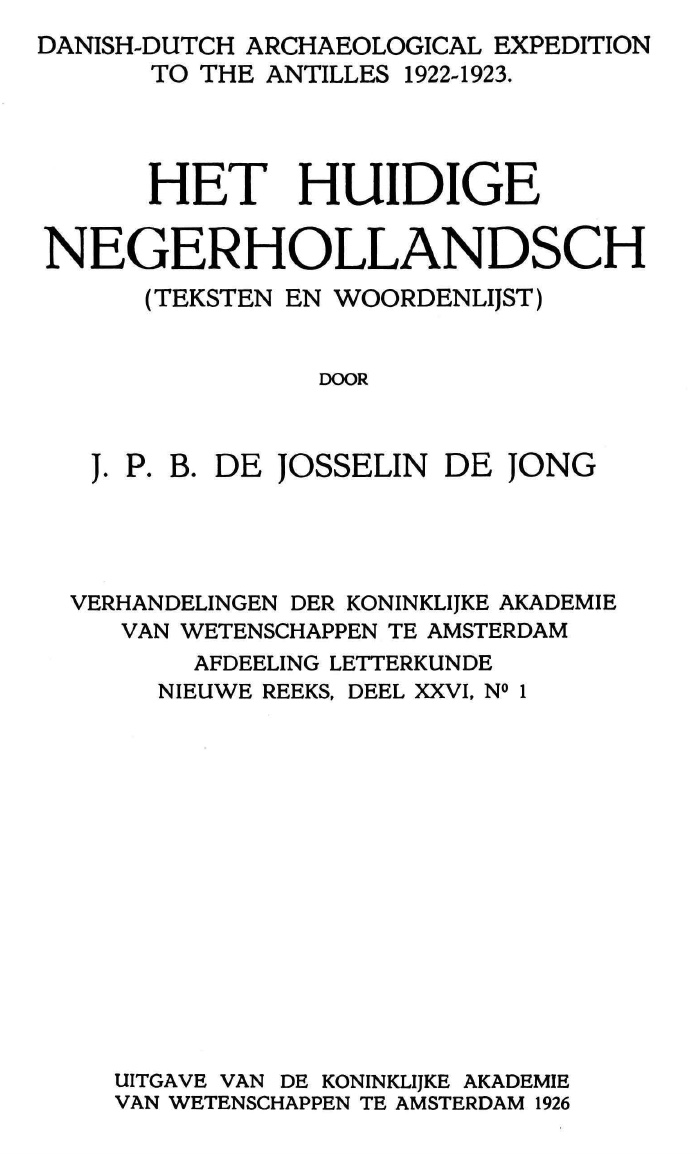

During an archaeological expedition to the US Virgin Islands in 1922/23, the Dutch anthropologist/linguist/archeologist J.P.B. de Josselin de Jong collected fairy tales and fables in Dutch Creole, which he got published in 1926. The narrators and informants were all born between 1841 and 1863, and thus were at least 60 years old at the time, which was a reason for de Josselin de Jong to speak about the language as “presently rapidly dying.” Most people on the islands, especially the younger generation, had switched to English and English Creole. That is why some referred to the language as ‘the old Creole’.

Earlier in its history, the speakers called the language “Cariolisch”, i.e., Creole, roughly translatable as the language of the locally born. Beginning in the 1840s, some scholars (i.e., European outsiders) used the term “Negerhollands,” i.e., “Negro Hollandic,” about the language. That term is now replaced by the academic term Virgin Islands Dutch Creole. The earlier name, abandoned in the 2010s, has racist connotations, obviously, but it is also factually incorrect: The language was not only spoken by Black people, but also by most Europeans in the islands. And it was not based on a Hollandic dialect, but on Flemish and Zeelandic varieties of Dutch.

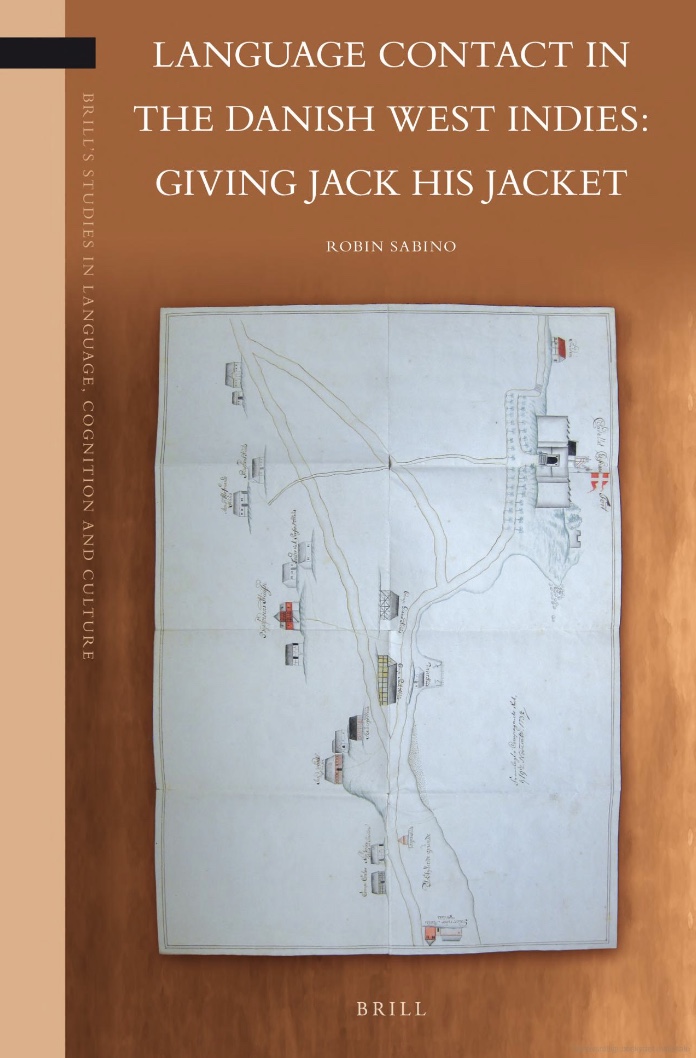

The span of documentation for Alice Stevens’ language is longer than that for any other creole language. It was documented for a period of 250 years, first by missionaries and later by linguists who did fieldwork. Robin Sabino wrote a book about Dutch Creole, published in 2012. Her main informant was Alice Stevens, whom she interviewed and recorded on tape in the 1980s. Although Dutch Creole changed, as all languages do, the last speaker preserved evidence of its original form, was Sabino’s rationale. Indeed, as another Virgin Islands linguist, Gilbert Sprauve, wrote about Alice Stevens, the Dutch Creole data produced by her was “the best yard stick for [linguistic] authenticity.” Sabino and Alice Stevens worked together closely. Stevens produced around 19,000 words for Sabino’s research, which have been preserved for posterity. Also Sprauve interviewed Stevens and made tape recordings of her speech. In one of his recordings, Sprauve invited Stevens to translate Grimm’s tale of “The Bremen Town Musicians,” which she then told back to him – and his tape recorder – in both Dutch Creole and local English Creole. Sabino remembers the following about the collaboration with her: “Mrs. Alice Stevens taught me Negerhollands. Without her quick mind and generous spirit, we would know far less about this language than we do.”

Alice Stevens’ contribution to preserving knowledge about Dutch Creole and local Virgin Islands cultural traditions was immensely important. When she died in 1987, Dutch Creole died out as a spoken language. However, a team of linguists and local Virgin Islands culture bearers and musicians – including Gylchris Sprauve, a relative of Gilbert Sprauve – meet weekly to try and reconstruct the pronunciation and the melodies of traditional Christian songs in Dutch Creole, that once were sung by the Virgin Islanders in their churches. Locally on the islands, there are individuals who are interested in learning more about the language and its history. In addition, the Dutch Creole specialist Cefas van Rossem has a treasure trove of a blog about the language, updated most weeks (https://diecreoltaal.com/). Thus, Dutch Creole, though extinct, is not forgotten.

The picture below shows linguist Robin Sabino (left) with language expert Mrs. Alice Stevens. The photograph comes from Robin Sabino’s 2012 book Language Contact in the Danish West Indies: Giving Jack His Jacket (p. 206).

Kristoffer Friis Bøegh works as Researcher at the Peter Skautrup Center and teaches at the Department for Scandinavian Studies and Experience Economy, Aarhus University.

Peter Bakker works as Lecturer in Linguistics at Aarhus University.

Thank You for the article.

A good reminder that language [like everythng] is fluid,malleable, and tidal.

Congrats Robin. Ian of Berbice and skepii dutch work hi Robin got to see that this is out one of these days I guess I’ll pass will cost again hope you’re enjoying retirement

This is my great grandmother thank you for posting this , I greatly appreciate it .

I have been trying to find this book! When I was 10 I did a painting of some palm trees, a blue sky and crystal waters for her. Now, my award-winning painting “Assassination Proclamation” has been dedicated to her.

My Grandmother.

Dear Cheryl, great that your grandmother played a role in your artistic development. Which book is it exactly you are looking for? Several are mentioned in the blog.

I was only aware of one by Robin Sorbino called, Danish language in the West Indies, “giving Jack his jacket??

I am also trying to get information on my grandfather, (her husband) i never met but, that is a different story.

My piece can be viewed at the guildofcreativeart.org jan, 2024 edgy show.