In June 2018, I (Peter Bakker) interviewed Ole Stig Andersen about the day he attended the funeral of Tevfik Esenç, the last man to allegedly speak the Ubykh language. It was October 7, 1992, 26 years earlier, that the funeral had taken place. In fact, Ole Stig Andersen had wanted to write himself about this funeral of a man and his language for Lingoblog.dk, and he wanted a text in at least three languages: Danish, English, Turkish. The text would have to be published together with the unique pictures he took of the funeral, and that have never been published or shown before.

He wanted to write no fewer than four articles in this connection: about Caucasian languages, about Caucasian minorities in Turkey, about minorities in general in Turkey and about the funeral itself. But he wasn’t quick enough to handle it. He had heard several times that he had only three months left to live (according to his doctors). I suspected that he would not be able to write the story himself. Therefore I interviewed him, so the story would be remembered. It was a trial interview, and that is all that we have, since the final interview never took place.

Ole Stig Andersen died in the summer of 2019. Below is a slightly edited transcript of our rather spontaneously organized interview. Lingoblog thanks Rane Schjøtt, who made the first raw transcript, Tevfik Esenç’s grandson Burcu Esenç for his courtesy and Ole Stig’s partner Bodil Rosenberg for her support.

Historical background

In 1864, Russia conquered parts of the Caucasus Mountains. The indigenous peoples there spoke Caucasian languages. Those languages are not related to Russian, and there seem to be several unrelated language families in the Caucasus. It is estimated that 600,000 people, all of them Muslims, fled to Turkey, where they would be safe and where they could practice their religion and culture. Many settled in a belt of crownland approx. 100 kilometers from the Turkish west coast. Around 25,000 of them were Ubykh. 130 years later there were no speakers of Ubykh left.

Peter Bakker

Caucasian languages in Turkey

Ole Stig Andersen speaks:

I had originally read somewhere, I can’t remember where, about this man in Turkey, who had moved there from the Caucasus. His language was said to be the language with the highest number of consonants in the world. That was such an interesting thing. During one trip in October 1992, we were all of a sudden close to his place of residence and then we decided we wanted to see him. Then we just took a bus and drove around. We wanted to see what was left of the native Caucasian languages in Turkey, because the Caucasians had fled – not all of them, but many of the small peoples there, to Turkey. They were only a few thousand each, and altogether some 20-30- 40 thousand – people. They fled when the Russians conquered the area.

Aage Meyer Benedictsen

For some time, people thought that the Caucasians in Turkey had disappeared as separate peoples, and also their languages. For a while they were believed to have died and disappeared and that were quite few. This was because these people were obviously unfamiliar with the settlement patterns used by the Turkish authorities. The Turkish authorities simply selected some areas in the country where they placed these refugees from the Caucasus, in large numbers. In this way, Aage Meyer Benedictsen, a Danish Jew and a strange man – or a man with many special rules and principles of the world, became involved. He was also a language genius. I want to say a few things about Benedictsen. He was a language genius – i.e. he was tremendously good at just learning languages quickly everywhere. Originally, he was trained as a linguist and he was supposed to hold positions in the Danish system, but he traveled all the time.

Back then, around 1900, traveling was very different, compared to today. He was armed and he had a guard. Everything took place on a bicycle and such. It was extremely strenuous. For some reason, he was very intrigued by it, so in reality these minorities were what he spent most of his life with. He traveled around the Middle East especially, but also elsewhere in India and Indonesia as a kind of scientific explorer. Sometimes he came back to Denmark. He was home for a while and then he traveled again. He continued to do so also after he got married with his wife. He left her, you might say, while he traveled around with a guard or guide. He arrived at the center of the Caucasus, and he discovered that the peoples believed to be extinct or disappeared from the Caucasus were, in fact, living in certain specific localities in Turkey.

Benedictsen’s disappeared notebooks

And there in Turkey he found the people. Among other things, he found some people who had contact with Caucasians, or who knew something about where they had gone from the Caucasus, and about the Turkish authorities with whom they had cooperated in a city. It was not where we found them, it is 100 kilometers further north from where Benedictsen found them. He wrote about them. What I first read was that he had kept a notebook, but later I understood that there were three notebooks. Those notebooks are then floating around in the stories between those Caucasianist linguists from that time. Who has them and who lent them to whom and so on? They have disappeared now, but they have disappeared in such a way that it may well still be somewhere. If the right person is identified, then they might show up; maybe they are in a Moscow library or in Saint Petersburg.

So somewhere they may still be, because of the the war, these things were spread. I haven’t actually researched it. Well, I researched what was in his archive, but a new batch has come a few years ago and I have not looked at it – it could in principle be there. Therefore it would actually be worthwhile to look up what is available now. Since the time I got home from there – it’s 25-30 years ago – something may have happened in the meantime and at least I know that something has happened within the last ten years. Things have been filed over the last seven years by the family. Maybe it lies there. We should investigate that.

PB: Where did they deliver it?

Ole Stig Andersen: To a body in Denmark that brings together important people’s written things after their death. The Royal Library, maybe. I don’t remember if it is there, but there is such a body that has collected things – as far back as they have been able to keep track of it at all. There have been previous submissions of Benedict’s stuff. The most recent filing, which is eight to ten years old, is also there. After all, I have not seen it and I do not know if there are any researchers who have looked at it, but it is delivered there.

OK, first people thought that the Caucasians were killed during the Russian genocide in the Caucasus. Bu then it turns out that they have fled across the mountains and have been located in a belt down through Turkey – from up close from Istanbul and down south. There are a number of villages that are Circasssian-Caucasian. And not only his tribe, Ubykh, also some of the other Caucasian tribes settled in that area. Their descendants are still there. You can talk to people and then they can tell that they are the son-in-law or something similar of some celebrity who originally lived in the Caucasus. I talked to them after all and there was a widespread desire, among some of them at least, who wanted that their children would move back to their homeland in what is now Russia.

Back to the Caucasus in Russia?

For example, I talked to a man who was trying to convince his son not to keep living in Turkey, he was to live in Russia. The son did not want to go to Russia at all. He thought it sounded like hell on earth to move to Russia. Poverty and oppression and everything else. Turkey, the son thought, was meaningful, but he did not want Russia. But the farmer saw it as a symbol of the family’s return to where they came from some generations earlier, so he more or less forced his son to agree to prepare to come back to Russia as a Caucasian of some sort – like Ubykh. But he wouldn’t, that kid. It was not his dream of the future to live in the Soviet Union, or in what it had become afterwards.

It was kind of funny, because he did not want it, but it was his father’s will. In fact, there are some of them who have returned after Russia has become more open. Some have returned, yes. But how their opportunities to live and settle and such, I do not know at all. But there are some who have returned. There was such a feeling that “we are Circassians and we have been displaced. We have not traveled voluntarily. This is our real country.”

The last man who spoke Ubykh

PB: You went there to visit a famous man who was the last one to speak Ubykh?

Ole Stig Andersen: Yes. That language, Ubykh, which is one of these Circassian languages, had gradually become extinct. Eventually it was thought that there was only one person left who mastered the language. There were some French – or maybe they weren’t French, for his name is not French but Circassian. [a Frenchman Georges Dumézil has written an Ubykh grammar etc.]

Some linguists, at least, those who were interested in them, looked for some of the last ones who spoke the languages, including Ubykh. Tevfik Esenç had worked for the municipality of Istanbul, I think, and when he was older, he became the mayor of his hometown. He lived down in the town we visited, called Hacıbektaş. It was him we wanted to visit because he had a birthday, if I remember correctly. At least we would visit him and he was old – something like 80 or something like that [he was born in 1904, so he was probably 88]. We thought it might be interesting to visit him.

He had passed away

Well, when we arrived there in the morning, we arrived with a bus where it turned out that all the people in that bus, without exception, were going to burial in the same village and for the same man whom we had planned to go and visit. Well, he had died early that morning – at about four or five in the morning – at the day when we arrived in the village, around noon. We, that is Bodil [Ole Stig Andersen’s partner, Bodil Rosenberg] and me. And they welcomed us like guests of honor – strangely enough, because we had never actually met the man and we did not even know him personally.

But because of the fact that we were foreigners and that we appeared to know something about the man, we made a big impression on the locals. The man had been very famous because he had made himself available to research and science. People had recorded things and he had been filmed and photographed and everything. Many of the things found around institutes that have an interest in Caucasian languages, are from him. They have recordings of Tevfik Esenç, who happily collaborated. Admittedly also for more unpleasant studies, for example when researchers injected powders in his mouth to see where and how the sounds were produced, because these languages have so incredibly many consonants, so many of them are very unusual.

Was he the last one to speak Ubykh?

It is of particular interest to investigate how to produce these consonants, and he was happy to help. Therefore he was honored and esteemed in scientific circles. He was a living language, you might say. And the last one, people say.

PB: Was he the last one to speak Ubykh?

Ole Stig Andersen: It is not easy to establish, because the term “the last” is a very unclear term. The last what? The last perfect 100% speaker or what? What if he was the last perfect speakers, but then, what about his son. Maybe he knew some of the language. What if he knew 50% or something like that? There is something fictitious about saying “the last one,” I think. Maybe you are the penultimate or the semi-final and his son can also say something.

It also turns out that people have not spoken with the women and there are actually four women over in another family who speak the language fluently. And so on.

But he was described in many contexts as the last person to speak Ubykh. And I think that that is simply not true, but he had the status of the last one who completely mastered it. I think that was also because he was willing to make himself physically available to science. They were allowed to drill and investigate and do research to investigate him and his language – especially the strange phoneme inventory that these Caucasian languages have – two vowels and 85 consonants.

PB: Can you articulate some of these consonants?

Ole Stig Andersen: Whether I can? No!

PB: There is hardly anyone who can?

Ole Stig Andersen: No, and I would think that if I did and was satisfied myself, then if there were native speakers, they would say that there is some aspect missing. I think.

The funeral

PB: Can you describe what happened when you arrived at the funeral? When you came by bus to the village?

Ole Stig Andersen: Yes, we got on the bus at 12 o’clock and then when we arrived it turned out that the man was dead – and we were told in the bus, but we did not know that he was dead when we left in the morning from Bandırma. We just wanted to do some sort of honor visit and I had bought a decent portion of locum for him and we just wanted to say hello. We had nothing but curiosity and respect for a man who was known for being the “last speaker” of the old language. And then the man appears to be dead. It is very exciting, you could say – from our point of view it is much more exciting that he had just died than if he had been alive, because if he was alive we would have just talked to him. But now he was dead, so now we could attend all the rituals associated with death and burial and all. That in itself was very interesting.

All the women sat in one house where there were only women and smaller children and there they were crying and things. No men were inside, only women and smaller children. So the sexes were completely separate for the funeral rites. All the men then walked to the cemetery where they were digging a hole so that he could lie down and he must lay in a certain way. So, when one is buried in the variant of Islam to which he belongs, the face must either face Mecca or east or – I don’t remember exactly how, but there are some rules about how they lay down. It seemed as if most of the men in the village attended the funeral, technically. So, in the pictures that we have, we see all sorts of people taking part in digging and arranging things and laying him down in the ground and that is how he is then placed.

After he was buried, the men in the family lined up – plus me and my partner, because we didn’t know what to do about ourselves. Then we stood there and said goodbye to around 150-200 people, almost in a row. So back in the village we were invited to eat some kind of funeral food that we then got there. It was not special food, it was Turkish food of some kind. Not rich food, not great food. If I look at my Turkish food, I can probably figure out what it was for something we got. It was some ordinary food, so nothing to write home about.

Women and strangers

And there were no women either. Only the men plus Bodil. She thought it was a pretty special experience. And a rare experience of course – suddenly being included, in fact with me, her being included in the funeral. And otherwise there were no women.

PB: Weren’t there some men who thought it was a little weird? A sign of concern from the others?

Ole Stig Andersen: Not that I know of. I met no raised eyebrows or anything. People did not seem embarrassed. I just think everyone seemed to believe that she does that because she is a stranger, so she doesn’t count. After all, those gender rules don’t really count with strangers. I have experienced this several times, also before. Even places where they are strict and separate, they do not separate men from women when you come and are Europeans. Then you are outside of that set of rules, in some way or the other.

The members of the family were standing there – the male members of the family, plus me and Bodil – and said goodbye to those 150-200 people who had worked physically in the cemetery to bury him. And then we went back to the hotel, or restaurant. Or it might not even be, it might just be arranged for that occasion. And then all the men ate there – plus me and Bodil too.

PB: So you don’t know where the women ate?

Ole Stig Andersen: No. And we talked about that if we would experience something like that a second time, when we are a little better prepared, then we would each go one’s way, then I could follow the men and Bodil would follow the women, that is what we know now. In fact, we do not know how the ritual was associated with the women, because Bodil was included in the men’s area with me, all the time. This is what happened in the afternoon. The man had died at four o’clock in the morning and we arrived with all the other guests at 12-13 o’clock with the bus. They had come to say goodbye.

To say goodbye

And then there was the funeral, and during the time people were digging and what else people did at the cemetery, it was getting darker and darker.

PB: It took a long time?

Ole Stig Andersen: It took a few hours. After all, many people also had to pay their respect. So, all those who were there – both those who helped and those who were just there – should all say goodbye or show their respect, at least, to his family. Hence there were a lot of hellos and goodbyes and everything else that needed to be arranged there. And where Bodil and me just joined. Thus, there were 200 strangers saying goodbye to us. It was a strange experience. And then there came people from near and far – many fine people also. And there came people with these arrangements, which are used in Turkey, where you have some about two meters tall arrangements with flowers in round rows.

Caucasians

It’s something I’ve seen in every possible place in Turkey, it’s nothing special Caucasian. Everyone does it, it’s something Turkish, something you do. People bring them, also well-off people. Thus people who come in an expensive car and are well dressed and stuff like that. I assume, if I remember correctly, that it was people from the Circassian leadership or people who were significant within the Caucasian environment – and they were not, after all, unknown to the other groups. There were some Ubykh people, but most belonged to other Circassian/Caucasian groups that appear, in such contexts here, as a large environment – a common environment.

I think there are maybe five or six different nationalities, all of whom are the same and together and they have a community as Caucasians. And then, as I said, he was buried and he had to face a certain direction. It was important that he was lying in the right way and that he was lying on his side, looking with his face in that particular direction, which was the right direction.

The coffin

PB: And when you arrived at the place, where was the coffin?

Ole Stig Andersen: The first thing we saw…. we both speak Turkish reasonably well, so we can get by in Turkish. It’s not good, but it’s workable. We asked for him (Tefvik Esenç), as we were not quite aware of what the event was like on this bus, and then we were guided to where he had lived. And it was there that, as I said, there were only women and smaller children.

All the men were in the meantime doing some things around the place where the funeral was going to be. And then the coffin stood maybe 50 feet from his house. He had also been a significant person in the local community because he was mayor for some time. I don’t know if he was mayor at this time, because he was in his 80s, so it has probably been in the past, but he has served as mayor of the villages – the Circassian villages. And they had a very pretty coffin, I thought. He was in such a coffin where there was a green cloth over the coffin and where there were things in Arabic letters that I couldn’t read.

Of course some Quran quote, I assume that has been said. In that way he had been there since he was found dead in the morning and then until he was buried later that afternoon. He wasn’t even outdoors for 24 hours. So, they found him in the morning – he had died at four or five o’clock – and he was buried at four or five o’clock in the afternoon. Twelve hours later he was buried. It’s pretty incredible that things are going so fast. And then people came from near and far, and there were also people who came late. In other words, people who had apparently left home when they heard about it, but when they arrived, he was already buried. And then people came up with these Turkish things, which are not particularly Caucasian, which I told about, that is, some decoration. It is a three-legged construction, it is two meters high and at the top is a round arrangement of flowers or imitations of flowers. And I’ve seen them many other places in Turkey, they have nothing to do specifically with the Caucasus. It’s a Turkish thing.

The funeral of the last speaker

PB: So you were one of the few linguists, who, one could say, has attended a funeral of someone who was the last to speak his or her language.

Ole Stig Andersen: Yes, there are not many. And Bodil was part of it – she has experienced the same thing. She’s just not a linguist, so she doesn’t really count. Yes, that is something I can say about myself.

PB: And how many people were there who took pictures?

Ole Stig Andersen: I don’t think there was anyone but me. I didn’t see anyone but me. Well, it was a Turkish farming community or something like that and people didn’t run around with cameras. After all, they would have done that if it had been in Istanbul, then there would have been young people with cameras. As far as I remember, I was the only one taking pictures.

PB: And you can’t see anybody with a camera in the pictures either?

Ole Stig Andersen: No.

PB: Surely those are the only pictures that are?

Ole Stig Andersen: Yes, I believe so.

PB: Now he is also famous as someone who was the last to speak a language. The last speaker.

80 consonants

Ole Stig Andersen: Yes, he was particularly famous at the time. If you dig deeper, you will find a few hundred of them anyway, but he was very famous. And I think that’s because he made himself available to researchers. And that his language was so extraordinary – two vowels and 80 consonants. After all, it is interesting. How the hell do you do that? I assume that many of them have sounded quite similar to my ears – that I couldn’t hear the difference between them. He made himself available and he traveled too.

A Norwegian

I saw somewhere that he had attended a conference in Norway on Caucasian languages. The man then traveled to Norway and, so to speak, made his throat available to science. I don’t remember the name, but yes. I have the name somewhere. Do you have a bid?

PB: Gunnar Fant?

Ole Stig Andersen: No. Somewhere in my old notes, it says what that Norwegian was called [it was undoubtedly Hans Vogt. He visited Ubykh villages in Turkey in 1958 and 1960, and also invited Tevfik Esenç to Norway. Vogt published an Ubykh-French dictionary with texts in 1963; PB]. And when he wrote about it then, he quoted a wrong year. He claimed that something particular had happened in 1894, which I later figured out couldn’t fit – it must have been in ’98 or something. You find such mistakes when you read the type of old material – that is, people do not sit and make sure 100% that what is remembered is remembered correctly.

Caucasian circles in Turkey

Then there was also a kind of respect or what to call it, which is used in Turkey, which came from different places, from the local Caucasian circles. And so they are a part of that – some of the Caucasians who fled in 1864 were placed in different locations in each village, I assume, in the area that was previously the area of the crown. It was not an attack on local Turks, it was the state that gave some of its goods to the refugees from the Caucasus. And there is one village of Ubykh people and the neighboring village is another nationality and the third and fourth and fifth of the various Caucasian peoples in such a belt. So if you have a map of Turkey here, a belt goes down, all the way from Istanbul in the north and I do not know how far down, but a bit down. The area in which these Caucasians were located is 100 kilometers or so. Traveling there from the coast was affordable.

PB: Two hours or something like that?

Ole Stig Andersen: Yes, something like that, I think.

The bus

It was very difficult, however, to find the bus because it was in Turkish way. You are asked when the next bus will run. Then you get one message and then you ask another person and you get another answer. And there are different messages, both about where the bus leaves and when it leaves. But I knew that – at that time I was experienced in traveling in Turkey, so I knew how to tackle it there. So I kept making sure to be at or near the place where someone claimed that a bus was leaving soon. And all of a sudden there was a bus to get off. Hey, hey, and two tickets and, off we go.

But we might as well have missed it. If we had stood in the wrong place or not heard properly or something like that. Then we had come with the next bus. More buses came after ours, it was not only ours. He was an esteemed man, after all. Well, he was a man of status throughout the Circassian circles. Also because of the respect that he had in circles of language scientists. On the other hand, he got another reputation just a stupid Caucasian. He was something special. Many people came from near and far and, as I said, some who came too late. Or, I don’t know if it’s too late, it might not even be, but those who came after the funeral, had ended up visiting the cemetery and people were sitting and eating something.

So we came by bus at 12-13, and then we were there all the time. We went back with someone in the evening back to the city by the sea.

PB: In a bus or car?

Ole Stig Andersen: I don’t remember that actually. I think we drove in a private car. I think we got a lift, Bodil and me, in one of the cars in which we drove back with, because when we came to Bandırma – and we must have done that, because we visited people there. That is, an organization or foreign workers association. And we wouldn’t have been able to do just that if we had come by bus. So we drove with some of them to Bandırma. And then we found a hotel, which is the worst I have ever experienced. The worst thing I have ever experienced. It was so inhumane, so it was just that you would rather sit up and not rent a room. It was so indescribably inhumane. But we were not assaulted. And then with the ferry the next day to Istanbul. And in Istanbul, there were also many of these descendants of Caucasians – also of the specific tribe, Ubykh. And there was a local representative from Ubykh – he said he couldn’t speak the language, but he did. So he could also utter some sentences – he could also say something. And then was the representative of the Ubykhs in Istanbul city.

We talked to him and helped to put some things in place and so on. It was like that for two days. It was a very interesting experience. That is about 30 years ago. And I remember it being in the month of October. That was in 1992.

This is how the story of the last man who spoke Ubykh and his funeral ends. Ole Stig Andersen’s unique pictures of the funeral can be found here on Lingoblog.

Peter Bakker is a linguist at Aarhus University. He has worked with several small languages an minority languages.

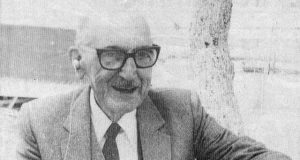

Ole Stig Andersen was a phonetician, immigrant teacher, journalist, translator and owner of a blog about minorities, languages and Turkey http://www.olestig.dk and the now-defunct blog The Language Museum.

Rane Schjøtt studies Spanish MA at Aarhus University.

Cenaze – Begrafenis – Begravelse – Funeral

https://www.lingoblog.dk/en/tevik-esenc-ubykh-cenaze-begrafenis-begravelse-funeral/