It was nothing less than a revolution that hit the world of Yiddish teaching this summer, when the multimedia Yiddish textbook In eynem (White Goat Press, 2020) was published. For many years, Yiddish students have been studying the language with Uriel Weinreich’s College Yiddish from 1949, or with Selva Zucker’s Yiddish: An Introduction to the Language, Literature and Culture from 1995.

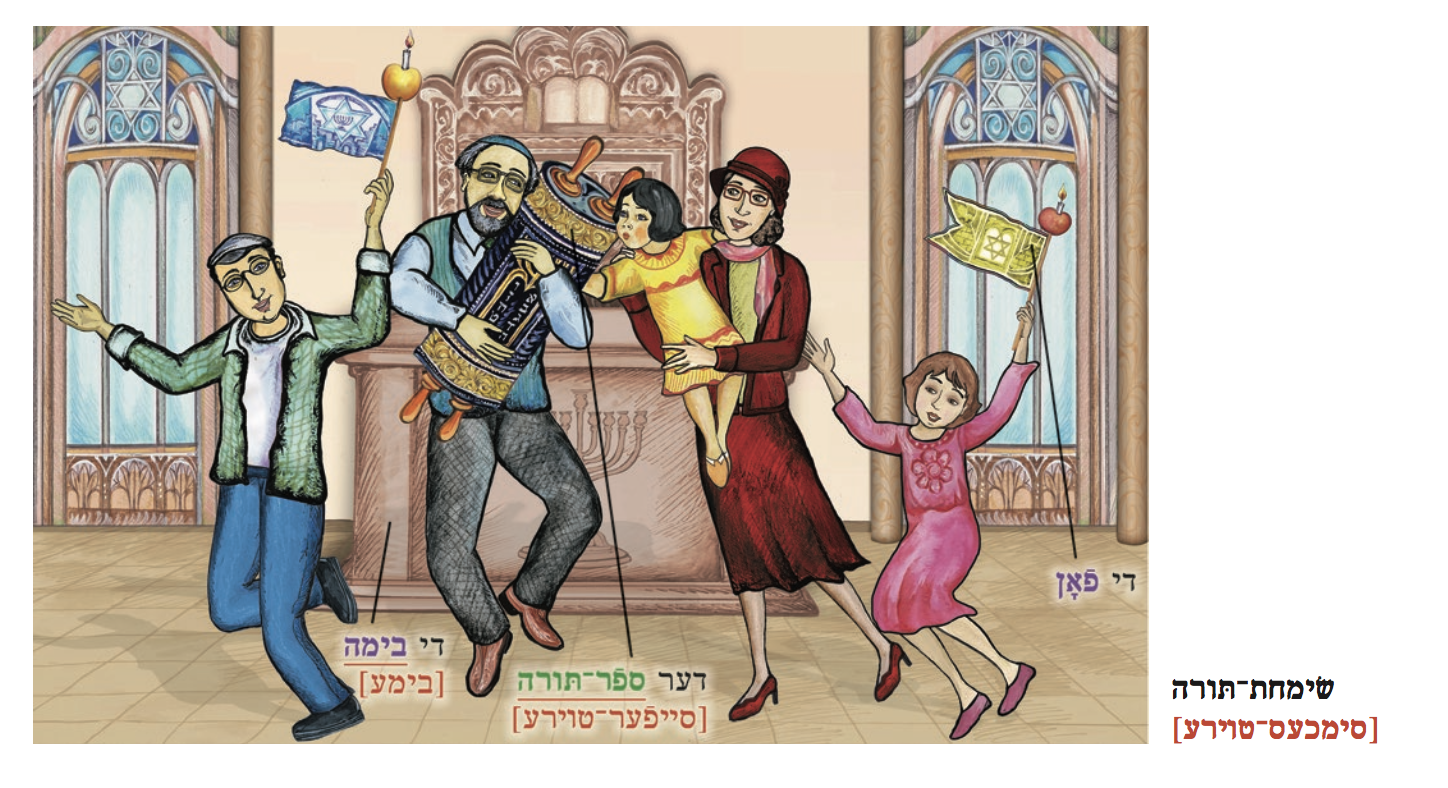

Now, Yiddish students and teachers have a more up-to-date alternative. In eynem is a monumental textbook, counting 800 pages (split up in two volumes), with beautifully illustrated dialogues, word explanations, exercises and texts about Jewish culture. It features a goldmine of material for the first two years of Yiddish studies. A dedicated website offers even more teaching material, e.g. additional chapters, but also a teacher guide and worksheets for the students. The pedagogical concept behind it is the so-called communicative approach, but the textbook can also be used for self-study.

Frank Gabel interviewed textbook author Asya Vaisman Schulman about this multimedia „Yiddishland“, about the reasons to study Yiddish today, about former Yiddish students’ careers, about Hasidic Yiddish and about how you can cultivate, preserve and live in Yiddish in a secular context in 2020.

One of the many interesting features of the textbook is its group of recurring characters, as they represent today’s Yiddish speaking community — both learners and (native) speakers of Yiddish. Could you tell us more about these characters? Who are the typical Yiddish learners and speakers of today?

There is a professor — Professor Etl Kluger — and her 11 students, who are all studying Yiddish. Each of the students has a different background, and they all represent groups of people who actually study Yiddish today. They come from many different countries: the United States, Canada, Poland, Israel, Germany, Argentina, and Russia. There are non-Jewish students, religiously observant Jewish students, and culturally Jewish students. There are graduate students and undergraduate students, and they study history, literature, linguistics, music, and various other disciplines. One of our goals with these characters was for people studying Yiddish to see themselves reflected in the book, which helps them feel more at home studying the language. Aside from the Yiddish class, there is an assortment of Yiddish-speaking characters standing in for people whom learners are likely to encounter in the Yiddish world: a Hasidic family in Brooklyn, a secular Yiddishist family in Manhattan, klezmer musicians, actors in the Yiddish theater, retired people in Florida, journalists who write for Yiddish newspapers, a former Hasid, an immigrant from the former Soviet Union, a professor of Yiddish in Japan. There are religious and secular people, people of color, and people of diverse backgrounds and identities, just as there are in the real Yiddish world.

Readers of your textbook are introduced to standard academic Yiddish. But they also get a taste of the other Yiddishes out there. What are these other dialects and sociolects of the Yiddish language and why is it important to expose beginners to them?

The main way that we expose learners to other dialects, sociolects, and an assortment of orthographies is through the authentic texts that are interspersed throughout the book. These texts come from a really broad range of media and sources, such as canonical literature, radio shows, newspapers and periodicals, films, oral history interviews, popular songs, and more. We learn about the phonetic differences between the three major dialect groups (Northeastern [“Litvish”] Yiddish, Southeastern [“Ukrainian”] Yiddish, and Central [“Galitzianer”] Yiddish) by listening to songs sung by speakers of those dialects. Students read the lyrics in klal (Standard) Yiddish, listen to the recording, and are asked to identify how the singer’s pronunciation differs from the standard forms the students have learned. We learn about different orthographies by printing facsimiles of older editions of Yiddish texts in the book and asking students to identify patterns in how word spellings differ from those they’ve learned. Both of these skills are absolutely critical for Yiddish students, because once they go out into the world of Yiddish, they will encounter many varieties of the spoken and written language, so it’s important for them to begin familiarizing themselves with the differences.

The biggest group of Yiddish learners and speakers is to be found in the Hasidic communities. Your textbook reflects that fact by including Hasidic characters in dialogues and exercises and by giving information on Hasidic resources. How does the Yiddish that the Hasidic communities are using and thus developing in their everyday lives influence the Yiddish you are teaching in your classes?

Although we could not include many direct excerpts of Hasidic texts in the book for copyright reasons, we did want to make sure that Hasidic Yiddish is represented in the textbook, both to cultivate a respect for contemporary Hasidic culture (as part of our general mission to give voice to the full range of Yiddish culture) and to facilitate future encounters with Hasidic Yiddish that the learner may have. The Teacher Guide in particular references Hasidic children’s books, CDs, and games that the teacher may purchase in Hasidic stores or online to share with students and offers suggested activities to do with these resources. For example, the chapter about weather references the Hasidic children’s book “Der guthartsiker shneymentsh” (The Kindhearted Snowman), and the chapter about body parts references music-and-movement songs from the Hasidic children’s CD series “Zing un shpring” (Sing and Jump). In the chapter about clothing, we include a facsimile of a Hasidic poster from Williamsburg cautioning against the wearing of brightly-colored immodest clothing and ask the student to engage both with the cultural implications of such a text and with the Yiddish dialect it is written in.

Although we could not include many direct excerpts of Hasidic texts in the book for copyright reasons, we did want to make sure that Hasidic Yiddish is represented in the textbook, both to cultivate a respect for contemporary Hasidic culture (as part of our general mission to give voice to the full range of Yiddish culture) and to facilitate future encounters with Hasidic Yiddish that the learner may have. The Teacher Guide in particular references Hasidic children’s books, CDs, and games that the teacher may purchase in Hasidic stores or online to share with students and offers suggested activities to do with these resources. For example, the chapter about weather references the Hasidic children’s book “Der guthartsiker shneymentsh” (The Kindhearted Snowman), and the chapter about body parts references music-and-movement songs from the Hasidic children’s CD series “Zing un shpring” (Sing and Jump). In the chapter about clothing, we include a facsimile of a Hasidic poster from Williamsburg cautioning against the wearing of brightly-colored immodest clothing and ask the student to engage both with the cultural implications of such a text and with the Yiddish dialect it is written in.

You have been working as a Yiddish teacher for several years now. Your experience with Yiddish students and the careers they are pursuing once they finish their studies may give some indication on how secular Yiddish will be developing in the years to come. Would you share some career paths of your former students with us? Are they working with Yiddish or using the language in other ways?

Students come to Yiddish classes for a wide variety of reasons. Some want to connect with their family heritage through the culture; some have academic interests in fields related to Jewish studies; others are interested in the linguistics of Germanic languages; still others are artists who want to authentically express their ancestral culture in their art; some are interested in the political movements that have a shared history with Yiddish. As a result, the role that Yiddish plays in their career paths also varies greatly. I have former students using Yiddish in a variety of ways: as professors of Polish and modern European history; as artists in the Yiddish theater; as songwriters who are setting Yiddish poetry to song; as Judaica librarians; as filmmakers and playwrights; as Yiddish tutors and Yiddish teachers themselves! Of course not all students end up engaging with Yiddish in their main professional or creative pursuits so directly; many of these students, however, still engage with Yiddish language and culture in their personal lives by attending concerts, lectures, and festivals, and socializing in Yiddish, among other things.

Students come to Yiddish classes for a wide variety of reasons. Some want to connect with their family heritage through the culture; some have academic interests in fields related to Jewish studies; others are interested in the linguistics of Germanic languages; still others are artists who want to authentically express their ancestral culture in their art; some are interested in the political movements that have a shared history with Yiddish. As a result, the role that Yiddish plays in their career paths also varies greatly. I have former students using Yiddish in a variety of ways: as professors of Polish and modern European history; as artists in the Yiddish theater; as songwriters who are setting Yiddish poetry to song; as Judaica librarians; as filmmakers and playwrights; as Yiddish tutors and Yiddish teachers themselves! Of course not all students end up engaging with Yiddish in their main professional or creative pursuits so directly; many of these students, however, still engage with Yiddish language and culture in their personal lives by attending concerts, lectures, and festivals, and socializing in Yiddish, among other things.

In your view, is there a chance that Yiddish — in a secular context — will make a comeback as a language, people are using in their everyday lives?

People are already using Yiddish in their everyday lives. It may not be a widespread vernacular outside of Hasidic communities, but for anyone who is interested in connecting to the language in any of the ways mentioned above, plenty of opportunities are available. My goal as a teacher and textbook author is to provide learners with the resources they need to make Yiddish their own and to guide them in exploring everything the culture has to offer. The majority of the world’s languages are in fact minority languages. I hope the resources we’re building for Yiddish demonstrate that there are many ways of cultivating, preserving, and living in a language that don’t require using it as your primary mode of communication.

„In eynem — The New Yiddish Textbook“ can be ordered from the Yiddish Book Center’s online shop. The introductory price for the two volumes is $100 (regular price $139).

Title: In eynem — The New Yiddish Textbook

Authors: Asya Vaisman Schulman, Jordan Brown og Mikhl Yashinsky

Publisher: White Goat Press

Year of publication: 2020

Pages: 800 (two volumes)

Price: $100 (introductory price)

Asya Vaisman Schulman is the director of the Yiddish Language Institute and the Steiner Summer Yiddish Program at the Yiddish Book Center (Amherst, Massachusetts). Schulman has taught Yiddish courses at Harvard, Columbia, the New York Workmen’s Circle, and Gann Academy in Waltham, Massachusetts. She holds a PhD in Yiddish from Harvard. Her PhD research was on the Yiddish songs and singing practices of contemporary Hasidic women.

Note: Morten Thing reviewed (in Danish) the world’s most elaborate Yiddish dictionary for Lingoblog.

Frank Gabel is a translator and freelance journalist. He blogs about Yiddish/Jewish culture at www.nayes.news.