The closure of Old Norse, Old Danish, modern Icelandic, and Faroese as elective courses at the University of Copenhagen is sad news indeed, that has also been covered also in the daily press. That this is a deeply misguided decision will almost certainly be self-evident to readers of Lingoblog.

Ideological absurdity

There is an obvious absurdity that the oldest university in Denmark will not offer medieval Danish. Or that a world-class Old Norse research institute (Den Arnamagnæanske håndskriftsamling) will no longer offer teaching in Old Norse. Or that the same institute, which is a joint Danish-Icelandic venture, should no longer offer teaching in modern Icelandic. I expect that I will not need to convince you either that this is unconscionable or that managerialism in Higher Education is to blame. So in what follows, I want to consider some of the ideological problems that this decision exposes: part of the story of how we got here, and where it might lead us.

Having taught Old Norse both in my native England, and also in America and Denmark, I have noticed that Danish students are unusual in that that there is always a small but noticeable proportion of them who assume that they will acquire Old Norse without too much bother – or indeed that they already somehow have an innate understanding of Old Norse before they’ve even done their first homework. I suspect this tendency even extends beyond the classroom to some extent.

Dane-splaining – unawareness of our own history

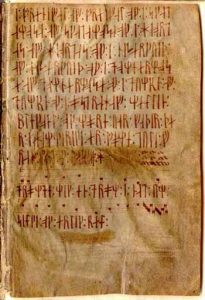

I recall as an exchange student in Aarhus many years ago propping up the bar in the student pub, reading Anthony Faulkes’s edition of Gylfaginning. I made some small talk with two law students, who asked what I was reading. They reacted with great interest, confidently proclaiming that all Danes had some understanding of Old Norse, as the languages were so similar (the students in question admitted they had never actually seen a sentence of Old Norse, but the mutual intelligibility of the two languages was common knowledge). I still recall the look of utter confusion on one of the young men’s faces when I offered him Faulkes’s edition to peruse, and how I felt almost guilty to be watching a long held assumption disintegrate before my very eyes. A cynic might object that this anecdote says more about law-students than Danes at large, but nonetheless the experience of being “Dane-splained” concerning matters to do with North Atlantic culture and history will be familiar to many non-Danish philologists (not that anyone would mind having such things explained to them by Danes who do have proper philological training, of course).

Þá mælir Gangleri: ‘Hvat verðr þá eptir er brendr er himinn ok jǫrð ok heimr allr ok dauð goðin ǫll ok allir einherjar ok allt mannfólk?’

Translated into English as:

Then Gangleri says: ‘What will remain when heaven and and all the world has been burnt, and all the gods and all the einherjar and all the human race are dead?’

Why should Danes feel that Old Norse already belongs to them?

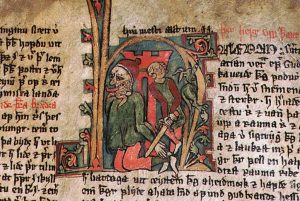

I suspect that a powerful combination of colonial ambition and heady Grundtvigian nation-building is the historic cause, even if today most Danes are unaware of this story. Iceland, where virtually all surviving West Norse manuscripts originate, was simply a county (“amt”) of Denmark for most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Administratively speaking, there was little to differentiate Iceland from, say, Jutland or Funen in the mental map of many Danes until the early twentieth century. Put another way, Iceland was subject to the colonial desire to control and appropriate. Just as British colonialism in the east ended up making the consumption of curry into an integral part of British identity, Danish colonialism in the north ended up making Old Icelandic literature an inalienable part of the Danish kulturarv “cultural inheritance”.

(As an aside, it must be noted that there were also Danish colonial projects in the east and indeed elsewhere in “the global south”. It might be tempting to infer that the Danish colony in Tranquebar [in Tamil Nadu, India] gave the Danes the curry which is today eaten in karrysild, boller i karry etc., although Danish curry infact came via the English colonial project – not directly from the Danish East Indies).

All reasonable British people will accept as an abstraction that curry is originally from India, but accepting this self-evident fact will not disturb their sense of personal attachment to it. A chicken tikka masala will never feel foreign to them. I suspect the same is true of Danes who enjoy the Icelandic sagas (to the extent that most Danes have ever read one – I suspect, like the law-students from the UniBar in Aarhus, many are more attached to the idea of reading a saga rather than actually picking one up and settling in with it for the evening). The appropriation of Old Norse runs deep: when heavy-weight Danish philologists of the 1800s such as Rasmus Rask, K. J. Lyngby, and Niels Matthias Petersen used the word modersmålet “the mother tongue”, it was often unclear whether they meant modern Danish or Old Norse, so tightly bound were the two in their minds.

Selvfedme

While I don’t think there are too many positive words to be said about cultural appropriation in general, I have to admit that it has at least been very useful for getting funding for philology. But I wonder if the same ideological engine which first made Danes interested in Old Norse is now contributing to its destruction as a learned discipline. Danish has a concept called selvfedme, which indicates a feeling of being rather pleased with oneself, and therefore coming to rest on one’s laurels and slide towards deleterious complacency and inaction. Even before the devastating news that subjects such as Old Danish and Old Norse were to be eliminated as options in the curriculum at the University of Copenhagen, many of these courses had been moribund: not enough students were signing up to take them, and they were meeting informally rather than officially. We must beware of the rhetoric of Free-Marketeers here; I am absolutely not saying that the lack of demand justifies the lack of supply (indeed, even if these courses had been bursting with students, I suspect that certain ideologues would happily see them gone). But I do wonder if the lack of student uptake might be related to a certain sense that a good Dane does not need to study Old Norse in a rigorous academic setting in order to know something about it. It is simply “in the blood”. “And if we already know about it, why do we need to have people to teach it to us? It won’t do any harm to close it down!” Is this selvfedme in action?

By way of contrast, here at University College London in the Department of Scandinavian Studies, we offer Old Norse, modern Icelandic, until recently Faroese, and a whole raft of medieval Scandinavian courses. An important part of this success is rooted in a flexible and sensible approach to minimum enrolment requirements – indeed, if the management at the University of Copenhagen stops enforcing arbitrary minimum student numbers for certain courses, then much of the threatened teaching there may yet be saved. Nonetheless, here at UCL we still drum up plenty of students and offer plenty of teaching. As far as I know, the same can be said of Scandinavian departments in Zürich, Berkeley, Wisconsin-Madison (though here under the banner of German, Nordic, and Slavic), and until not long ago could be said of Berlin and Edinburgh (both of which have kept Scandinavian Studies but scaled back their investment in its medieval dimension). It can certainly be said of the University of Oslo, which has become quite a powerhouse in Old Norse teaching and research. In the case of British and American universities, there is a larger population base than in Denmark – though this is less true of the Swiss or Norwegian examples, given that Denmark has around 6 million inhabitants, closer to Norway’s 5 million or Switzerland’s 8 million. It is tempting to infer that not having Old Norse as a taken-for-granted part of ones kulturarv seems to encourage young people to seek out good quality teaching in that subject.

Having Old Norse as a part of ones kulturarv doesn’t seem to have been calamitous for the state of Old Norse philology in Norway (one wonders whether the occasionally slightly neurotic desire for Norwegians to locate their country in the past has helped here – lavish quantities of oil money can’t have done any harm either). But in the case of Denmark, something seems to have gone badly wrong – and to have been going badly wrong for some time even before this unwelcome announcement.

Of course, it would be both offensive and myopic to say that the greatest blame lies with Danish selvfedme – as I said at the outset, it is very obvious that the managerialist, pro-business, pro-free-market assault on universities is the major contributing factor. Since 2016, Greek has no longer been available as an official course at the University of Copenhagen, and Ancient Greek came within a cat’s whisker of closure (which would have made the University of Copenhagen the only university in a European capital not to offer it). Finnish, Indic Studies, Indonesian, Polish, Thai and Tibetology all ceased accepting new students to read these languages as core programmes around the same time, effectively meaning they have been closed. Icelandic, Old Norse, Old Danish and Faroese would appear to be the latest victims of the same process. As universities and government ministries for education increasingly collude with organised capital, they seek to eliminate minor subjects which do not contain an obvious route to “making better employees”.

Why study small languages?

One might try to address the KPMGs and PricewaterhouseCoopers of this world on their own terms, and make a case for why studying a small language does make you a better employee. But I’m not terribly interested in doing so:

1) I’m not at all convinced that captains of industry really know what they want,

2) even if they did, I’m not convinced they would stick to it – the Tony Blair government in the UK spent years getting universities to offer vocational courses, often working closely alongside industry to design them, and many industries now aren’t interested in students who studied those courses,

3) even if they did know what they want, even if they could stick to it, there’s no reason to believe that what’s good for capitalism would be good for human happiness.

I’m not going to say that learning Old Norse makes you a better employee because for all I know it does not – but it does stand a good chance of making you a better person. Studying any small language allows us the opportunity to see the world from outside the perspective of the mainstream.

(Ironically, some of the language programmes closed by the University of Copenhagen are not even for small languages. Indonesian has nearly 200 million speakers – and is mutually intelligible with Malay which has nearly another 200 million speakers. It therefore has over 30 times as many speakers as Danish, and almost twice as many as German)

The brutal past

Most native English-speakers know the story of Custer’s Last Stand at Little Big Horn – but if you speak Lakhota, you’ll have a better chance of understanding the story from the other side as well. If you read Old Jutish, you’ll be able to read the Jyske Lov, and you’ll know more about Danish history than somebody who has to rely on another’s translation. Lots of people watch the television show “Vikings”, but people who read Old Norse tend to know a lot more about the reality of life in the Viking Age, and I suspect they understand better the ideologies which the show tacitly tries to sell to them.

In fact, I would suggest that part of the tragedy of these closures is that Old Norse and its related disciplines, far from being nationalist fripperies, are in fact needed more than ever. While the so-called Alt-Right (a subculture more than an ideology) merrily appropriates the Scandinavian kulturarv with abandon, the irony is that people who have actually read Old Norse literature will know that it calls into question modern assumptions about notions like race, liberty, and indeed the whole concept “Western Civilisation”. The Sagas of Icelanders (Íslendingasögur) and the Contemporary Sagas (samtíðarsögur) depict a society brutally tearing itself apart after a fatal overdose of individualism. The Chivalric Sagas (riddarasögur), and even more so the Indigenous Romances (lygisögur), reveal a complicated conception of ethnicity, where at the same time concepts which approach modern Orientalism and “colourism” overlap with a conviction that the people of the North should aspire to the wealth and sophistication of the Middle East. And while Old Norse literature naturally encourages a dialogue with mainstream European thought, it also reveals that for much of its history, the North has never really been a part of the West.

By closing down the teaching of Old Norse, Old Danish, modern Faroese and Icelandic, the University of Copenhagen has elected to replace knowledge with selvfedme. Abroad, the damage to its international reputation has been immediate and painful. As for the damage decisions such as these may cause at home in Denmark itself, I am reminded of a saying uttered by Gréttir Ásmundarson in the great Icelandic Grettis saga (c. 1320):

“Verðr þat, er varir … ok svá hitt, er eigi varir.” – “The foreseeable happens … the unforeseeable too”.

Richard Cole is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the Department of Scandinavian Studies, University College London. From August 2018 he will take up the position of Assistant Professor at the Institut for Kultur og Samfund, Aarhus Universitet.

Further reading

On use of the term Modersmål:

- N.M. Petersen (1845) Det oldnordiske Sprog som Undervisningsgjenstand i de lærde Skoler

- K. J. Lyngby et al. (1863) Offentlig henvendelse om modersmaalsundervisningen

- Marie Bjerrum (1959) Rasmus Rasks afhandlinger om det danske sprog. Copenhagen: Dansk videnskabs forlag

- Paul Diderichsen, Ed. (1937) Fra Rask til Wimmer. Otte Foredrag om Modersmaalforskere i det 19. Aarhundrede. Copenhagen: Gyldendalske boghandel

On how far industry has failed in designing useful skillsets for the workforce:

- David Graeber (2018) Bullshit Jobs. A Theory. London: Allen Lane

Det kan også læses på dansk på lingoblog.dk

Og her:

https://uniavisen.dk/ragnarok-paa-koebenhavns-universitet/