What is grammatical gender?

Grammatical gender is a fascinating feature of language. Not every language utilizes it, and those that do, might not necessarily agree on noun classification systems or assignment of gender to nouns. For example, English has no grammatical gender, Spanish utilizes a masculine-feminine dichotomy, and German has an additional neuter gender. Apart from categorization of biological gender, such as “the man; the father” (Spanish: el hombre, el padre; German: der Mann, der Vater) or “the woman; the mother” (Spanish: la mujer, la madre; German: die Frau, die Mutter), grammatical gender is seemingly arbitrary. This means that various non-human, inanimate objects are assigned a gender, without any logical reason. The categorizations are random, as different languages sometimes assign opposite grammatical gender to the same noun. For instance, an apple in German is masculine (der Apfel), while it is feminine in Spanish (la manzana). In German, the sun is feminine and the moon is masculine, while it is directly opposite in Spanish.

Because grammatical gender is a syntactical feature of language, – i.e, definite and indefinite articles such as ‘the’ and ‘a/an’, as well as adjectives (eg, ‘red’, ‘small’, ‘powerful’ etc.) have to be conjugated in concordance with the inherent grammatical gender of the noun – speakers of a language with grammatical gender always have to be aware of the gender of the words they are uttering. It is therefore a feature of language that is quite demanding and important, and learners of a language with grammatical gender may find it difficult to navigate such a system, especially if they are native to a language without grammatical gender.

Linguistic relativity – the idea that language impacts thought

In a context of cognitive science and psycholinguistics, the question of whether language can impact thought has been debated for centuries. The hypothesis is referred to as linguistic relativity – and proposes that grammatical features and other uses of language may have an effect on cognitive processes, such as conceptualization, memory, or perception. Various studies have been conducted, testing for how humans across the globe conceptualize domains such as time, (for example, in which way does time move?), colour categorization (eg, Russian has two words for blue, while other languages just have one), and one particular interesting case is that of grammatical gender. In the early 2000’s, Lera Boroditsky and her colleagues asked the question: “If speakers of various languages categorize certain words as masculine or feminine, does this mean that the speakers also conceptualize and think of these words as being more or less male-or female-like?” To illustrate this idea, does the sun seem more like a woman to German-speakers (die Sonne) and more like a man to Spanish speakers (el sol)? In an experiment, they asked speakers of German and Spanish to describe inanimate and concrete objects with adjectives, such as bridges and keys. All of the nouns in the experiment were categorized with grammatical gender that were directly opposite between the two languages.

They found that German-speakers perceived their grammatically masculine keys as “hard”, “jagged”, and “useful”, while the Spanish-speakers perceived their grammatically feminine keys as “little” and “intricate”. Meanwhile, German-speakers described their grammatically feminine bridges as “beautiful” and “elegant”, and Spanish-speakers perceived their grammatically masculine bridges as “big”, “sturdy”, and “strong”. It seemed as though the grammatical gender assignment in the different languages had impacted the speaker’s cognitive conceptualization of words, making them focus on characteristics that are tied to gender stereotypes. These findings indicate a potential effect of language impacting thought.

Throughout the last two decades, especially in recent years, many have aimed to replicate this experiment or elaborate similar experiments, testing for the linguistic relativity hypothesis. Some have found similar results, some have found mixed evidence, while others have found no such indications. However, almost all of these experiments have utilized concrete objects, that is, things we can see, hear, touch and so on.

But what about abstract concepts?

Hans Larwin, 1917

Example of death (masculine in his language) represented as a man

These lack any direct ties to reality or sensory-motor information. Abstract concepts, such as liberty, death, time, or love, exist because we have language to define them. Because these words are more dependent on language than concrete objects, it has been hypothesized that linguistic relativity (language impacting thought) would see a more notable effect in the cases of abstract words.

A particularly promising case is the cognitive process that we call personification. The human mind actually has a hard time understanding and visualizing abstract concepts, which also explains why young children learn these words later than concrete objects. Research has shown that talking about or depicting abstract concepts as personified entities help us better understand, remember, and conceptualize those words. For example, one might say “when life gives you lemons, …”, even though life is not literally able to give, as it is not an animate being with its own consciousness. We personify non-human entities and concepts on a daily basis, without even realizing it.

One very concrete example of personification, where biological gender is involved, is in anthropomorphic visualization. For example, if you would imagine ‘time’ as a person – what would they look like? This is a feature that has been heavily utilized in various arts and cultural artifacts, such as paintings, figures, and statues. Now, the question is, if a language utilizes grammatical gender, can this impact the visualization and personification of abstract concepts? If the word for time in a language is feminine, such as in German (die Zeit), do speakers of this language then imagine time as a woman? And likewise, if grammatically masculine, such as in Spanish (el tiempo), do speakers conceptualize time as a man?

Death, Love, and Liberty

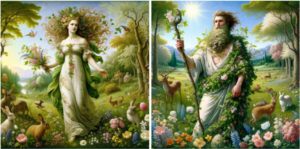

Taras Shevchenko, 1844

Example of death (feminine in his language) represented as a woman

In 2011, Borodtisky and Segel analyzed more than 700 personifications in art from Italy, France, Germany, and Spain. They concluded that “Grammatical gender predicted personified gender 78% of the cases…”, a very high impact of language on cognition. Perhaps this is why the Statue of Liberty is a woman, as ‘liberty’ is a grammatically feminine word in Latin and all of the romance languages. It may also explain why “love” is depicted as a male figure (Cupid/Eros) in classical Roman and Greek mythology, as the words were both grammatically masculine in both languages. This poses an interesting question, that grammatical gender may not only influence our individual perception of abstract concepts, but perhaps also entire cultures, mythologies, gods and goddesses and other types of folklore. One interesting example is the depiction of death. In western European cultures, it is often the male figure ‘The Grim Reaper’ that symbolizes death. In German, death is grammatically masculine (der Tod) – but even in English and Danish, languages that used to have grammatical gender, death was also grammatically masculine. Meanwhile, in Slavic cultures, death is often depicted as a woman, sometimes called ‘Marzanna’ or ‘Morana’. Notably, the words for death in slavic languages are grammatically feminine.

Experiment A: How do people describe abstract concepts?

I wanted to test this hypothesis following the methodology of Boroditsky’s key-and-bridge experiment. I asked native speakers of German (34) and Spanish (37) to freely describe various abstract concepts with three adjectives. I presented them with 10 abstract words, two were emotions (anger and love), two were seasons (spring and winter), two were human creations (art and music), and the remaining four were infinity, death, time, and peace. The grammatical gender of these words are contrasting between Spanish and German, except for music (feminine in both) and winter (masculine in both).

The 71 participants generated more than 200 adjectives. I chose the 15 most frequently mentioned adjectives, and a third, Danish-speaking segment then rated the adjectives on a binary scale of stereotypically ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’. Some examples of adjectives were ‘beautiful’, which was rated very feminine, or ‘quick’ which was rated as more masculine. I then analyzed the data to see whether the participants had applied characteristics that follow gender stereotypes in congruence with the grammatical gender of the abstract concepts.

I found two interesting indications:

Firstly, a mixed evidence argument for somewhat of an effect of linguistic relativity. For example, the adjective ‘warm’ was rated as 77% conceptually feminine. Upon describing the word ‘love’ (feminine in German, masculine in Spanish), German-speakers used the adjective ‘warm’ twice as often. Yet, in other cases, it seemed that individual or cultural factors played a greater role.

The second finding was an indication that both German and Spanish-speakers consistently used emotional words to describe abstract concepts. In fact, more than half of the most frequent adjectives were related to emotions – some examples are ‘sad’, ‘aggressive’, and ‘happy’. This is in line with current research which states that emotions are fundamental for the conceptualization and acquisition of abstract concepts. After all, how can one understand the idea of inequality, if they cannot feel anger? Or the concept of hope, if one cannot feel anticipation and joy?

Experiment B: How do people personify abstract concepts?

I used the latest, accessible AI technology at the time (March, 2024) to generate images depicting personified abstract concepts. Each of the 10 words were represented with two versions: a male and a female figure. I then asked the Spanish and German-speaking segments for each abstract concept: Which depiction do you think fits this word best?

The results indicate that grammatical gender appears to reinforce the perception of allegorical or conceptual gender. For example, although in both segments ‘death’ (feminine in Spanish, masculine in German) was generally preferred as a male figure, German-speakers consistently chose the male figure 97% of the time, while Spanish-speakers chose it 78% of the time – a discrepancy of almost 20 percentage points. Likewise, for spring (feminine in Spanish, masculine in German), where the female figure was selected 94% of the time for Spanish-speakers, Germans selected the same figure 79% of the time. This is an interesting finding and may indicate that grammatical gender is not a determining factor, but rather a contributing factor.

Although there seems to be some indication that grammatical gender affects various aspects of cognition, such as perception, personification, and conceptualization, it seems that linguistic factors are not the strongest or most defining features in these processes, at least when applied to abstract concepts. If we were to argue a notable case for linguistic relativism, it is crucial to establish the consensus that grammatical gender does not determine cognition, nor is it the only factor influencing perception and other cognitive processes, and finally, it does not seem to be the most present or dominant type of influence either.

Otis Arnevik Lilley just finished his master’s degree in Spanish and Latin American Language, Literature and Culture, with a minor in English at Aarhus University. Growing up bilingual, and continuing to learn various languages, he has always had a deep interest in linguistics, cultures, and psychology. He has specialized in the field of interdisciplinary linguistics and cognitive science, dedicated to researching the idea that language may impact thought – particularly with the case of grammatical gender. Language, being perhaps the most uniquely human concept to exist, is a great perspective from which to understand our emotions, psychology, cognitive processes, and ourselves. Otis dreams of pursuing a PhD, continuing to research current topics of psycholinguistics and the frontiers of the linguistic relativity hypothesis.

Native speaker of German here; not surprised.

The effect may be stronger with animals. All snakes are female unless and until proven otherwise – in German.