Lingoblog continues to provide you with suggestions for your summer readings on various linguistic topics. This week we have found a book about fieldwork.

As a linguistic fieldworker you typically travel to a remote place to live with a tribe, you are adopted into the community and you learn a language in order to document and describe it. So you take on many different roles. First and foremost, you’re a linguistic researcher, trying to uncover patterns in an underdescribed or perhaps completely undescribed language. You’re also a data archivist, ethnologist, technician and administrator, just to name a few: fieldwork involves the collection and storage of high-quality data in an ethical manner, typically with ample administrative and bureaucratic hurdles to overcome.

But you’re also simply a human. You’re part of your own culture, you’ve been shaped by your environment and history, and you have a certain personality. Needless to say, linguistic fieldwork is likely to have a sizable impact on you as a person, and it is often a mix of joy and turmoil. You get to see remote parts of the world, become part of a community and solve intriguing linguistic puzzles, but there are also some obvious discomforts regarding climate, diet, isolation, and often a complete lack of luxury, which most fieldworkers deal with to some degree. All this is life-changing, and usually in a good way in hindsight. But then there are those situations, fortunately much rarer, where you find your very life at risk: diseases, tsunamis, accidents, kidnappers, terrorists, and so on.

‘Microphone in the Mud’ is a book written by linguistic fieldworker Laura Robinson. It deals with all of these aspects: the joy, excitement and academic satisfaction of travelling to a remote place to describe a language, peppered with discomfort, sickness, miscommunication, uncertainty and, in her case, a number of life-threatening experiences.

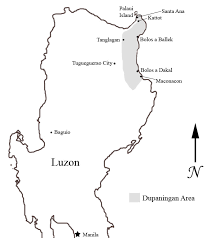

The book follows the author during her first-ever fieldwork, in the Cagayan province of Luzon, which is the largest and most populated island of the Philippines. She would stay in the region for almost a year to document and describe the Dupaningan Agta language, which is one of many Austronesian languages spoken in the Philippines. Her objectives were to write a dictionary and a grammar book, and record hundreds of hours of Dupaningan Agta speech. She had already taken two years of courses in Tagalog, the national language of the Philippines, and over a year of Ilokano, the regional language of the Luzon Island, which she would have to use to communicate with the Agta people.

Her fieldwork starts in Santa Ana, a municipality in the extreme north-east of the island of Luzon. This would be her main base, where she would stay at a guesthouse, and from where she would try to get into contact with the Dupaningan Agta community. She soon meets speakers of various varieties of Agta, one of which is Dupaningan Agta. She records and writes down words in all of these varieties, and her linguistic research has officially taken off. This is how a lot of fieldwork begins: the researcher starts out in an urban area and comes into contact with people who know speakers of a certain language, or they find speakers who have moved away from a rural community to a more urban area, perhaps forming a small offshoot community. But to really start working on a language, the fieldworker has to go to the speaker community and spend time there. In Laura’s case, she had to find Agta camps in the jungle.

She quickly finds someone willing to take her to the Dupaningan Agta camp, where she meets a man named Gregory. He proves to be a good and helpful informant, and teaches her a lot of his language. The community is glad to have her, and they build a house for her. She starts documentating and describing the language in the camp, with Gregory as her main informant. The bulk of the book follows Laura during the process of documenting and describing Dupaningan Agta, travelling back and forth between the Agta camp, where she conducts her research, and a homestay in the urban area, where she processes her data, buys groceries, and runs various types of errands. But it is certainly no plain sailing, and the story is littered with unfortunate events, ranging from situations causing minor distress to outright dangerous situations. There are the dangers of the Sana Ana Centro, the odd drunk taxi driver, dishonest people, and unreliable and greedy language informants. And she also catches malaria and ends up in the hospital. The medication she is given, however, leaves her with violent and paranoid thoughts. And then there are the more pleasant experiences: the Agta community is welcoming and curious about her, she makes friends at a church youth group, she was a witness to the world record of the longest fish grill in the history of the world, her parents come to visit, and her dissertation is slowly taking shape.

But things take a nasty turn when she meets an Ilokano man named the Treasure Hunter. Not only is he most likely part of a group of people involved in shady activities, such as illegal logging and fishing with electricity, he is also suspiciously eager to meet her. And since she knows the New People’s Army terrorists were active in the region and had a habit of kidnapping people, she was careful. And with good reason – as it turns out, the Treasure Hunter has every intention of kidnapping her. What she doesn’t know, however, is that one of her most trusted informants would betray her to this man. What follows are desperate attempts to stay safe as she attempts to bring her research to a good end.

I like this book for several reasons. It is a thrilling description of a young woman’s travels, and does a great job of taking the reader along to this remote part of the world. It pays attention to detail, and conveys the scenery of Luzon, the differences in culture, and the general feeling of adventure nicely. Not only is this an account of Laura Robinson’s field trip, however. Many of the chapters contain passages about linguistics in general. Various passages, for example, explain why linguists are so eager to document and describe languages.It also becomes clear why, from a theoretical point of view, it is worthwhile travelling to remote parts of the world to write grammar books about exotic languages. Other topics dealt with in such passages are for example how data archiving works, how to make a dictionary, what the documentation of languages can tell us about human history, and much more. These are written in such a way that non-linguists can easily read them and get a good idea of why linguists busy themselves with such tasks. Other passages deal with the Philippines and its history, languages and peoples, and provide the reader with a helpful context to the story.

I highly recommend this book. It is in my opinion one of the better accounts of a linguistic field trip, providing a nice mixture of thrilling events, linguistic and other academic context, and the author’s experiences from a more personal point of view. It is highly readable for linguists and non-linguists alike, humorous at times and gripping at others, and strikes a nice balance between the exciting, the informative and the personal. The book can be downloaded for free here.

Jeroen Willemsen is a researcher at Aarhus University in Denmark. He has conducted fieldwork on Reta, a Timor-Alor-Pantar language spoken in Eastern Indonesia, which he was recently interviewed about for Lingoblog. Coincidentally, Laura Robinson is also one of the few people ever having collected data on Reta. You can find words collected by both Jeroen and Laura at LexiRumah.