As of November 2020, the territories where native Armenian speakers live have become smaller. Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey, launched a war against the unrecognized territory of Artsakh (also known as Nagorno Karabakh), inhabited by ethnic Armenians. As a result, a large part of Artsakh was given to Azerbaijan, and ethnic Armenians had to leave their homes. Many of those displaced families had roots in the area reaching back centuries.

Being displaced from ancestral homelands is no news to Armenians. Within the past two hundred years Armenians have been through a genocide, various massacres and pogroms by Turkey and Azerbaijan. There is even a word for “eviction of Armenians” in Armenian – հայաթափում (“hayatapum”), where հայ (“hay”) means “Armenian” and թափում (“tapum”) is the nominalization of the verb թափել (“tapel”, “to spill”). If you wonder why this happens, instead of writing another article about the history of the region, I’ll give you keywords like expansionism, colonization and pan-Turkism. Add to that denialism, revisionism and impunity and you get a hayatapum of more and more territories.

Before digging further into the Armenian language, let’s first place the country on the map. The Republic of Armenia is located in the South Caucasus and has borders with Turkey to the west, Azerbaijan to the east, Georgia to the north and Iran to the south. Linguistically, this is quite interesting. Armenian, being an Indo-European language, is surrounded by countries that have their official languages belonging to three different language families, with Persian being the only Indo-European language, Georgian belonging to the South Caucasian family, and Turkish and Azerbaijani belonging to the Turkic family (and in fact so closely related that they are mutually intelligible). To make matters more complicated, all these languages have different scripts. Armenian uses the Armenian (alphabetic) script. Georgian also has its own alphabet. Turkish and Azerbaijani use the Latin script, whereas Persian is written in the Persian script, which is derived from Arabic.

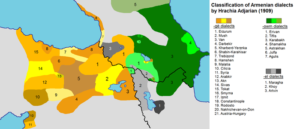

The South Caucasus and the neighboring areas are linguistically and ethnically rather complex. Apart from the official languages spoken by the respective countries, one can encounter many other languages belonging to the Indo-European, South Caucasian and Turkic families. The Armenian language itself, being an independent branch of the Indo-European family, has two standard varieties – the Eastern and the Western. Historically, Eastern Armenian has been spoken in the territories largely controlled by Russia and in Iran (currently the territories of Armenia, Artsakh, Azerbaijan and Iran), whereas Western Armenian has been spoken in what is now Turkey and Northern Syria. After the Armenian Genocide in 1915, the number of Western Armenian speakers in Turkey dramatically dropped and thus the survival of the language was left to the Armenian communities in other countries, such as Syria, Lebanon, France and the USA. In 2009, however, UNESCO classified Western Armenian as a “definitely endangered” language (“children no longer learn the language as mother tongue in the home”). Eastern Armenian, on the other hand, being the official language of the Republics of Armenia and Artsakh, does not face such threat, at least at the moment.

Despite being mutually intelligible, the standard forms of Eastern and Western Armenian have significant differences in terms of phonology, grammar and lexicon. While they both have a small number of vowels, Eastern Armenian has 30 consonants and Western Armenian has 25 consonants. This difference is due to unaspirated voiceless stops and affricates having disappeared in Western Armenian, whereas Eastern Armenian has a set of three consonants for each place of articulation: voiced, aspirated voiceless and unaspirated voiceless. Despite this seemingly small difference, it can often lead to misunderstanding. For instance, Armenians like to laugh about the male proper name Գագիկ (“Gagik”, some Armenian kings actually bore this name). Eastern Armenians pronounce it as /ɡaɡik/, whereas in Western Armenian it would be /kʰakʰiɡ/, which means “a tiny poop” in Eastern Armenian.

Both Eastern and Western varieties are morphologically rather complex. Nouns have cases (four in Western and five to seven in Eastern Armenian, depending on which linguist you ask). Verbs are marked for person, number, tense, mood and aspect. If you want to have some linguistic fun, I highly recommend digging into Armenian participles and trying to count how many tenses you can construct with them.

Interestingly, some morphological forms have different grammatical functions in Western and Eastern Armenian. For instance, կսիրեմ (“ksirem”, spelled as կը սիրեմ in Western Armenian) would be the first person singular conditional future for the verb “to love” in Eastern Armenian, but first person singular indicative present in Western Armenian. This, too, can cause misunderstandings, if the interlocutors have not been exposed enough to each other’s varieties.

Both Western and Eastern Armenian have a large number of dialects, which in certain cases may not be mutually intelligible. My great-grandparents, for instance, are either genocide survivors (Western Armenian speakers) or from Artsakh (Artsakh dialect speakers, which is an Eastern dialect). The Yerevan dialect that is my native language is quite close to the standard Eastern Armenian. While I am very good at understanding standard Western Armenian, I understand almost nothing in the Artsakh dialect (despite roughly similar amount of exposure). The Artsakh dialect is one of the oldest Armenian dialects. It has an extra set of vowels and palatalized consonants that standard Eastern Armenian does not have. Additionally, many words in the Artsakh dialect are directly inherited from the Proto-Indo-European language and some others are loans from Russian, Turkish and Persian.

With large parts of Artsakh having gone through hayatapum and the remaining part currently being under Russian control, the number of Artsakh dialect speakers will also drop in the years to come. This dialect may have the same fate as Western Armenian. Therefore, it is necessary to make efforts to preserve it. As long as there are Armenians living in parts of Artsakh, the dialect will remain alive.

Byurakn Ishkhanyan is a psycholinguist. Between 2018 and 2021 she was connected to the “Puzzle of Danish” project at Aarhus University. She is currently working as a postdoc at the University of Copenhagen. She is also a trained medical doctor and an author of a short story collection.