This post is a rewritten version of my paper for the course ‘Postcolonial Linguistics’, offered at Linguistics at Aarhus University in the autumn of 2013. I wanted to delve into different language attitudes towards Sheng – and what better way to do it than through Youtube video comments?

Sheng? WTF?

Sheng is as a language variety of Swahili – a mixture of Swahili, English and a host of regional languages of Kenya. The grammatical structure stems from Swahili while incorporating terms from English and indigenous Kenyan tongues (e.g. Dholuo and Kikuyu). Consider the following example (adapted from Abdulaziz and Osinde 1997:56):

Kithora ma-doo za mathee

steal PL-money of mother

‘To steal my mother’s money.’

Here, kithora stems from the Kikuyu word kuthora (steal), madoo comes from the Swahili slang donge (amount of money) together with the plural prefix –ma. Mathee is a Sheng rendering of English mother. These elements have been slightly altered to create a distinct Sheng appearance while retaining the meaning.

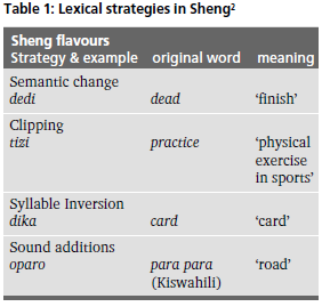

Sheng can also be classified as a slang variety primarily spoken by the youth. Originating from the slums of Nairobi around 1950, Swahili speakers started producing this new blend of slang, code-switching between English and Swahili. This code-switching can take place on different levels, both syntactically and morphologically. The table below (from Meierkord 2009:6) shows different lexical strategies of code-switching.

What’s the data?

The data considered here consists of comments from Youtube videos focusing on Sheng and the language situation in Kenya. All the comments are from 2010-2013, but most videos have been taken down since then – so unfortunately all the quoted comments are without references. The video comments illustrate the way in which Sheng is portrayed in the Kenyan media.

I found two discourses within the data – one of Sheng as a deteriorating factor and the other a discourse concerning Sheng’s role in national unity.

Discourse 1: Is Sheng deteriorating?

The first discourse that has been identified is language deterioration, where the main view of Sheng is that of a negative influence on the lives of its users. This view is already salient in the title of one video, Learning Curve: Sheng affecting children’s language skills. The feature concerns the language skills of children in Kenya, where teachers worry that the use of Sheng will inhibit the acquisition of Swahili as well as English. With the initial description of the influx of Sheng as ‘the deterioration of language today’, the broadcaster commences the feature by placing Sheng in a negative light; as something that reduces the value of other language forms. This view is repeated in another feature where Sheng is said to be ‘killing languages in schools’ and that it has ‘eroded the value of languages’.

Certain comments echo the views behind the media position; one user finds the variety ‘horrible’ and states that ‘sheng is not good for the future of these kids, they cant even get a job as broadcasters both regional and nation,it pushes them further to poverty’ . Here the comment predicts that Sheng will lead to a bleak future for the coming generation, a future of unemployment and poverty. Another user also speaks doom of the generation of tomorrow: ‘my generation grew up writing proper English and Swahili these kids have no hope in hell they go home sheng, turn tv, sheng. Losing battle!’ This user further dissociates himself from the usage of Sheng by claiming that ‘his generation’ was fully apt in the country’s two lingua francas while the youth of today have no choice but to speak Sheng, an inferior language in comparison to English and Swahili.

Another pattern in this discourse is the reference to similar slang varieties and cultures in other parts of the world. Wasike (2011) investigates how Sheng permeates the Kenyan hip-hop culture and how this culture fosters a desire and an aspiration towards the American lifestyle, making Sheng an even clearer western-oriented language choice. Meierkord (2009:5) also notes that youngsters in the urban centers of Kenya increasingly identify with a ‘global hip-hop culture’. This relation to the West is not only viewed as positive. Remarks such as ‘i do meet some who even if you speak to them in swa (Swahili, ed.) will respond in English with a hip hop twang’ enforces the negative association with hip-hop, and others fear that the quality of English in Kenya will plummet so that ‘we will soon be speaking nigerian English-i hope not’ .

So, the deterioration discourse maintains that Sheng is the cause of poor performance in schools, prohibiting people from getting jobs, pushing Kenyans into poverty and ultimately preventing social ascent. Furthermore, Sheng is an inferior language belonging to the street, i.e. the lower social sphere.

Discourse 2: Is Sheng unifying?

A bulk of the comments claim that Sheng is a factor of unity: ‘if it was not for Sheng speaking in my school, alot of us kids would have been tribally divided’ . This is also repeated with reference to tribal groups, which are seen as something to be conquered and defeated: ‘this is the only way that we can beat tribalism’. The reason for the dissociation with tribalism may stem from the political turmoil that Kenya experienced in connection with elections in 2007. Here, differences in ethnicity proved one of the factors that spawned social unrest across the country. So when the users phrase Kenyan ethnic groups as a problem that can be solved by Sheng, this may be the reason why.

More pragmatic approaches to dealing with Sheng focus on the pride that it instills in them and the social benefits that it entails: ‘there are occasions when i switch to flawless (but always outdated) sheng to communicate more directly with people on the street. I am rather proud that i can do that and we should not discourage the only language that we have been able to develop in the last 100 years’ Apart from the individual pride, emphasis is also put on the wide spread and the inclusivity of Sheng: ‘anybody who is below 40’s speaks sheng, at this rate it simply means that it is only a while before everyone from the elderly to the new borns start speaking sheng’ This comment has a certain impassive ring to it, that this proliferation of Sheng is inevitable and that the only reasonable action is to embrace it – or maybe recognize it from a more scientific viewpoint: ‘Sheng is now and emerging language that should also be standardized and be examinable’.

The notion of language as a resource has apparently gained a footing in the popular media of Kenya; through articles in magazines and in hip-hop music getting air time in radio shows. Through these channels, the language is able to exist and prosper while at the same time reaching various segments of society, not only the lower class. Another spreading channel of Sheng is through sites such as Sheng Nation, a page on Facebook dedicated to the language. Here one can find a Sheng-English dictionary, possibilities for users to create new definitions of Sheng words, song lyrics etc.

The bigger picture emerging from the analysis is that Sheng is thriving within the youth, especially in the hip-hop environment as well as on the internet, the radio and in magazines. It can exist laterally with Swahili and English, giving no reason to consider it a deficit. Lastly, the notion of Sheng as solely a youth language is maybe bound to change, with more and more youngsters growing up without leaving Sheng behind. They are still ‘performing youth’ through their speech, but for how much longer will it be considered youthful? With the growing focus on the written form of Sheng and the desire to promote it further through various medias, this slang variety maintains its position as an urban lingua franca on par with English and Swahili.

Benjamin Riise teaches Danish as a second language at Lærdansk Favrskov.

Cover picture: Sheng Nation, a page on Facebook dedicated to use and spread of Sheng.

Further reading

Abdulaziz, M., and Osinde, K. 1997. Sheng and engsh: Development of mixed codes among the urban youth in kenya. International Journal of the Sociology of Language (125): 43.

Mazrui, A. 1995. Slang and Code-Switching: The Case of Sheng in Kenya. In: Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 42,168-179.

Meierkord, Christiane. 2009. It’s kuloo tu: recent developments in Kenya’s Englishes. English Today 25 (1): 3.

Momanyi, Clara. 2009. The Effects of ‘Sheng’ in the Teaching of Kiswahili in Kenyan Schools. Journal of Pan African Studies 2 (8): 127.

Wasike, C. 2011. Jua Cali, genge rap music and the anxieties of living in the glocalized city of Nairobi. In: Muziki, journal of Music Research in Africa 8(1), 18-33.