Few people who walk into the buildings of Aarhus Cathedral School, the red and the gray, are aware that someone who once spent many hours studying here went on to being world famous. And even better that the basis of this fame was founded at the Cathedral School, in an area of study unknown to most people.

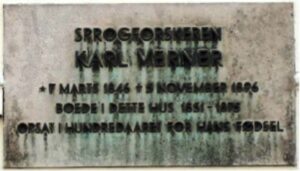

Few of the students rushing along Vestergade in Aarhus on their way to school even pay attention to the memorial plaque on the gray house number 5: “The linguist Karl Verner 7th of March 1846 – 5th of November 1896 lived here from 1851 to 1875”. Today there is a shoe store and a fur store on the ground floor, but from 1857 to 1864 Karl Verner used to live here while attending school at the Aarhus Cathedral School. Every day, Karl Verner would walk along Lille Torv (Small Square) past the cathedral to get to school. Today it is hard to imagine how this short walk would have looked at the time. There were no colourful advertisements, and the stores were small and without well-lit windows filled with ads.

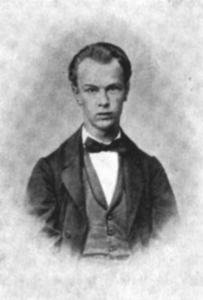

Karl Adolf Verner was born on the 7th of March 1846 in Aarhus as the second of six boys. His father was a German immigrant, a sock weaver and later clothing manufacturer Friedrich Wilhelm Werner (1820-1876). His mother, Catharina Dorothea Hansen (1817-1873), was born in Roskilde and grew up in a custom official’s home in Kalundborg. As the only one in his family, Karl Verner decided to make his German surname Danish-sounding because of the Prussian-Danish war in 1864.

Karl Verner’s name is part of the world of international science, and anyone working with the history of language will surely be familiar with his discovery.

For most people at the Cathedral School, Karl Verner is unknown. There is no memorial plaque on the wall reminding them about his great discovery and about the reputation his name has.

Karl Verner’s Law – “The discovery of America”

Karl Verner was no politician nor statesman. Still, he had a law named after him: Verner’s law, which is a term to describe a regularity within the history of language. Here it is described as follows: The exception to the first German sound shift. It was a problem in the development of language that had perplexed linguists well before the beginning of the 19th century.

Suddenly, Karl Verner found the solution to the problem and he was at once world famous. Some linguists have even compared the significance of his theory with the discovery of America. Something that might make this all the more interesting is the fact that this discovery was made in the street called Vestergade in Aarhus.

Verner’s discovery is quite simple: At the time, people could not explain why modern words like the German Vater and Bruder had either a <d> or a <t> in the middle. The original Indo-European consonant in the middle of both words, <t>, had become <d> and <t> respectively. Still, the question was why. Because of this, it was simply called an exception to the first Germanic sound shift. The first Germanic sound shift had taken place at around the year 1000 BC in the Germanic languages and with that decisively removed the Germanic language family from other Indo-European languages. But until then, no one could explain the reason for why <t> had split into <t> and <d>. Karl Verner phrased the law as follows, and since then it is called Vernerian change: The Indo-Euopean language originally unvoiced consonants /p, t, k/ had become voiced when the Indo-European accent was not placed on the previous syllable. Today, we find this rule in German grammar, for instance schneiden – geschnitten. Karl Verner’s big achievement was realizing that it was all due to the prosody and stress. One can of course think that this is not relevant in today’s world. That there are other questions out there more important to answer. But let me interject here that knowledge of the past makes predictions about the future possible.

Let us in the following look at Karl Verner’s own explanation of the problem, which he, one night in Tivoli, has shared with another world-famous Danish linguist, Otto Jespersen (1860-1943). The reader is asked to please note the free and clear language, which Otto Jespersen has done his best to retain. The thoughtful way to describe the problem shows part of Karl Verner’s way of being and the modest nature that came to define his life:

“I was in Aarhus and was incidentally not quite well at the time. So one day I wanted an afternoon nap and randomly chose myself a book to help me fall asleep. Coincidentally, this turned out to be Bopp’s “Vergleichende Grammatik”, and you know that the Sanskrit words in that book are written with a special raised font, making them impossible to avoid seeing. I opened up the book to a page where my eyes caught the two words pitår and bhråtar and that got me thinking that it was strange that one of these words in Germanic had a <d> and the other one an <f/z>, that which shows in the difference between the German Vater and Bruder – and then the accents in the Sanskrit words caught my eye. And you know the state where one is almost about to sleep, there the brain works best, that is when you have new ideas and you are not constrained by all the habitual connections we have while awake. Now I had the idea – could it not be that the original accent was the reason for the different consonants? Just after that thought, I fell asleep. However, that same night I was to write a letter to Julius Hoffory. At the time, we were eagerly coresponding about linguistic questions, and since it was now my time and had nothing else to write, I told him about the accent. The next morning, I thought about it again and thought that it could not possibly be right, and I almost wrote Hoffory saying that he should not concern himself with such nonsense, but then I thought no, let him rack his brains with disproving it. But then when I was about to have my afternoon nap that day, I found Scherer’s “Zur Geschichte der deutchen Sprache” by chance, and there I saw his explanation, that the irregular sound shift were found in more commonly used words, at by that of course I saw that it was utter nonsense for since when should the old Germans have used <fadar> or <modar> more than <brother>? And then I started testing whether the Sanskrit accents that Bopp had indicated were true, and when it was I speculated on and since found at first one and then another example that fit my observation.”

Julius Hoffory (1855-1897) was another student from Aarhus who became a linguist, and a classmate of Verner at the Cathedral School, with whom he corresponded frequently. Hoffory died as a professor in Berlin. (Readers who wish to know more about Verner’s law are referred to the long obituary about Karl Verner in Tilskueren 1897, where Otto Jespersen in his own clear manner explains the complicated theory of language).

Lingoblog is celebrating the summer by sharing with you the biography of the world-famous linguist Karl Verner in four parts. This is just part one, so be sure to read along next week where you get the change to read more about Verner’s school years as well as his time as a student, both in Denmark and abroad.

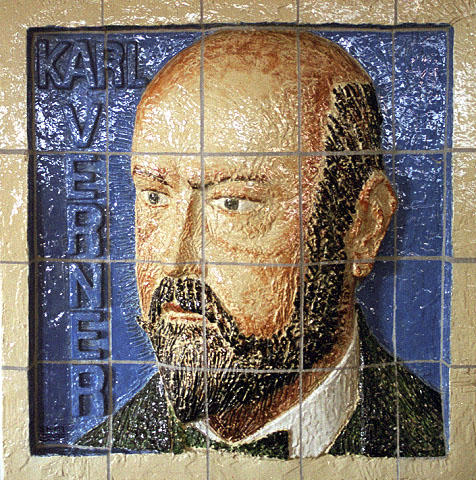

Frontpage picture: The sculptor Knud Nellemose’s stoneware relief. On display at the Verner-room in Nobelparken, Jens Chr. Skous Vej, Room 366, Building 1481.

The article “Karl Verner – A world-famous student” has previously been published in the book Aarhus Cathedral School, 1195-1995, edited by Finn Stein Larsen. Aarhus: Aarhus Cathedral School, 1995.

Lars H. Eriksen. Born in 1957, graduate with A-levels in modern languages from Aarhus Cathedral School in 1976, studies in Nordic, linguistics, Germanische Philologie as well as studies in law, tax law and economy at the University of Aarhus, Universität Düsseldorf, Universität Bayreuth and University of Southern Denmark. Cand. phil i dansk 1982, Ph.d. 2001 on a dissertation on “The language of the court in Denmark and Germany” (“Sprache vor Gericht und in der Verwaltung”) – Associate professor in Danish in Bayreuth 1980-90, law. in Bavaria 1990, then Rechtsreferendar in Bayreuth, employee at law firms in Düsseldorf, Saxony and Bavaria. 1996-2001 University lecturer in Danish and German at the cross-border studies in Sønderborg and Flensburg. Collaborator on international language projects on language policy and language law; tax law, EU corporate tax law and criminal law. Employee at the European Commission on International Social Security. Now working as a tax consultant in international affairs in South Schleswig. Has written articles on German and Danish language matters, language teaching and legal topics. Publisher of several Danish-German dictionary works within law and tax / annual accounts 2016-2021 latest:

– Juridisk ordbog tysk dansk, 380 sider. Ny udgave 2021

– Juridisk ordbog dansk tysk, 380 sider. Ny udgave 2021

– Ny regnskabsordbog dansk – tysk 305 sider. Ny udgave 2021

With exemplary translation of Danish annual accounts.

– Ny regnskabsordbog tysk – dansk 256 sider

With exemplary translation of German annual accounts. New edition 2021.