A definition of history I heard recently is that it is the discipline concerned with the writing of the science of change in past events and human affairs. Born in South Australia, I am surrounded by documentable change and evidence of previous happenings.

This article considers the fishing ground names — wet placenames — located offshore to the north from Penneshaw and American River as local Kangaroo Island ephemera and historical capital of parochial importance.

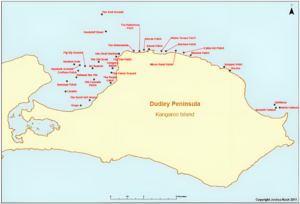

I chose Dudley Peninsula, Kangaroo Island, in 2009 as a comparative island case study for my toponymic research toward my PhD in linguistics at the University of Adelaide. Dudley Peninsula has a colourful and varied placenaming history. My brief was simple: compare the placename data from my major toponymic study of Norfolk Island, where I had already been two times by the time I first conducted research on Dudley Peninsula in February 2009, to what I would collect in and around Penneshaw and on the rest of the peninsula. During my first days on Kangaroo Island and in Penneshaw, it became clear that there was a similar system of naming fishing grounds (Figure 1) to what I had documented around Norfolk Island.

Here was an aspect of placenaming that had scarcely been documented in the literature. Apart from some popular descriptions of colloquial names for fishing grounds in coastal South Australia I had come across, my research was to my knowledge the first documentation, popular or academic, of fishing ground placenaming in the state. Within these 54 previously unrecorded names and their cartographic and mapped tapestry as a flat map in two-dimensional space lives an account of neighbourhood-based narrative of fishing history, a name-inscripted cartographic imprint of the area’s personage of history and its offshore lifestyle, culture, and humour, and elements of how names grip to landscape-cum-seascape against the passing of time. It is almost like these names want to be recorded, that their essence is crying out a desire to be remembered, not lost. Such work requires someone to bear witness — historian, linguist, ethnographer, or whoever — to precipitate this element of oral culture and collective memory.

Fishing is an important livelihood and defining cultural activity on Dudley Peninsula. However, modern GPS technology and a decreased dependency on fishing mean that many of these names are a quickly fading memory. Mark Kurlansky’s depiction of pioneering fishermen in North America illustrates the need to document the cultural significance of fishing ground names against the inevitability of loss over time:

Only today, having forgot a pencil [for documentation], they head over to the other boat where the three-man crew is already hauling cod with handlines. After a few jokes about the size of this sorry young catch, someone tosses over a pencil. They are ready to fish.

Many Dudley Peninsula fishing grounds are shallow reefs and crevices found through exploration and trial and error. It became clear during interviews on island that people are aware of the existence of such fishing ground names and their use. However, most people do not themselves know the names, the history of the names, e.g. who named them first and who continues to use them, why they were named, and where fishing grounds are located. This could be because of several reasons, the most obvious being lack of usage or loss of memory and secrecy. Dudley Peninsula fishing ground names exist within the placenaming of a people who are connected to sea and land for their livelihood. Handwritten journals and scratchy accounts are rare. Mental records are the main extent of the extant, documentable pointers. I am making previously invisible archives visible, turning the obscure into the distinct.

Places like No Reason came into being through trial and error from actual fishing experience. These names were passed down through generations. They exist as non-exact and transient offshore locations created through intimate knowledge of the sea and events:

Jeff Howard stopped the boat one day when he was out with Shorty Northcott, put the anchor down and people asked, “Why did you stop the boat?” and Jeff said, “No reason”. This is one of the best fishing grounds in the area and it is still used today. It was named approximately 20 years ago and is about half a mile out from shore. (Shorty Northcott, personal communication, Dudley Peninsula, 2009)

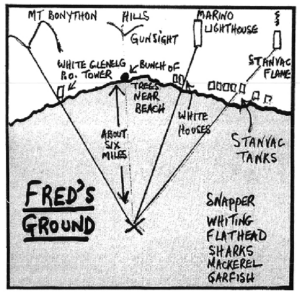

Dave Capel’s book, 50 Favourite Offshore Fishing Spots, gives a description of Fred’s Ground, named after the shark which was once seen in an area, offshore from Adelaide (Figure 2), illustrates how names of fishing grounds prior to GPS have been located and remembered.

Knowledge of these fishing marks is exclusively the realm of elder community members, typically men. Few women fish offshore around Dudley Peninsula, so they have less access to fishing ground knowledge. Typically, their knowledge consists of a few common names they overhear when spoken by male relatives or associates. Much of this knowledge has been passed down to the fishermen from family members. Modern tracking systems, sonar, and GPS have rendered a lot of the spatial orientation and name information obsolete.

Kangaroo Island fishing ground names depict aspects of insider knowledge and locational information associated intrinsically with the land and sea. Fishing is an important livelihood and a defining cultural activity in this remote island community. Kangaroo Island’s fisher folk use an intricate system of naming and locating areas at sea. This system is extremely accurate and existed long before GPS technology. To locate a fishing ground or patch, the fisher has to know approximately how far out at sea they are. They then take two visual markings, lining up obvious facets of the landscape that can be seen offshore. These two marks form a triangle with the offshore point being the location of the fishing ground. This primitive method of triangulation is very precise and reliable. Fishers will never let anyone know their marks lest they give their favourite spots away to others. When interviewing fishers on Dudley Peninsula, I often had to reassure my informants. “I don’t want to know your fishing spots so I can fish there. I really just want to know the names and what they mean. I’m a linguist, not a fisher,” I would say.

A couple of Kangaroo Island fishing grounds are: Between the Tits — a ground known to a few local fishers. Off Kangaroo Head, it uses the space in between The Tits, a local placename describing the undulating landscape in the area, in lining up the ground. An old name, it has been used for ages. The Purple Patch is just a couple of hundred yards out from shore. The area at sea appears purple due to an underwater reef there. It is a great fishing spot and the name alludes to the expression, ‘you’ve struck a purple patch,’ meaning ‘you’ve done well’.

As the now late fisherman, Nils Swanson, narrated to me in February 2009 in his quiet and remote shack in American River, “the fishing ground, The Gums, is in the American River area, just off the coast. It’s about 400 metres north-east from Edgar’s Ground. It was named such as some big gum trees in by Deep Creek were used as marks. It was named by locals around World War II. Eight hundred metres back from The Gums you come to The Front Door Patch. It was named by the old timers a long time ago, as you use the front door of The Burnt Out House in the mark. From The Front Door you go out 400 metres to the south-west and you come to Gray’s. It was given that name because Gray, a butcher on Kangaroo Island, had built the house. It’s a really old name.” I have tried my best to register and archive Nils’s sharp memory and locational prowess of these offshore locations in many of the placename membranes-to-deeper-knowledge in the map in Figure 1.

These fishing ground names, locations, and associated folklore serve as historical, geographical, and cultural markers of identity and place for Dudley Peninsula residents and the Kangaroo Islanders. They depict a past time and are a precise orientation system that does not require any devices save local knowledge, a sound memory, a good eye, and no fog. The names of boats, fishers, events, and locational information, all merge in this esoteric, ephemeral, and subtle process of placenaming.

On Dudley Peninsula I interpret an extensive complex of name, place, and people links built up over time, connections made available only to those allowed access to family properties and onshore and offshore fishing places. I travelled to the island twice as a PhD student. I moved within and across wet and dry landscapes. The map I created in Figure 1 remains as a linguistic and historical artefact, a map, language-in-place as spatial representation, and an aesthetic marker of cultural selfhood impounded within the Dudley Peninsula community. The Dudley Peninsula fishing ground name record represents a microcosm of naming, history, change, and scientific endeavouring. Names like No Reason symbolise and concretise toponymic and spatial composite into an account of language, landscape, and history within cartographic and mapped boundaries. Toponymy provides pointers as to how humans learn to speak about, manage, and orientate themselves in new and unfamiliar environments, with Kangaroo Island providing an excellent case study for learning about unofficial naming and understanding the history of settlement, land use, and events in South Australia.

Suggested reading

Hercus, L., Hodges, F. and Simpson, J. (eds.) 2002. The land is a map: Placenames of indigenous origin in Australia. Pandanus Press and Pacific Linguistics: Canberra.

Nash, J. 2016. ‘Dudley Peninsula: Linguistic pilgrimage and toponymic ethnography on an almost–island’, Shima, 10(1): 109-115.

Nash, J. 2013. Insular Toponymies: Place-naming on Norfolk Island, South Pacific and Dudley Peninsula, Kangaroo Island, Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Joshua Nash is a linguist, writer, and permaculturalist. He reckons he has a pretty cool modern furniture collection. He is the editor of Some Islands (someislands.com).