We just can’t let that tower go, can we? When it comes to linguistics in pop culture, and to conlangs in particular, there’s no getting around the Tower of Babel. Chants of Sennaar is a video game released in 2023 by the French studio Rundisc, and it does not bother with sublety when taking its influence from the story of the Tower of Babel. But the confidence is well-earned, as it puts a spin on the story’s themes and makes great use of the medium’s interactivity and the unique opportunities that conlanging provides.

This is part two of a serial about conlangs – i.e. invented languages – and their role in the world of video games. Part one can be found here.

Last week, I discussed how the more experimental approaches to conlanging in video games is mainly found in smaller game studios, and Rundisc gives us a prime example of this. In Chants of Sennaar, you control a hooded figure moving up through a tower in which each floor is inhabited by a new people speaking a new language. Armed only with a notebook, you start the game with no explicit information about any of these languages, and your task is to decode enough of each language to understand the people and texts around you, giving you access to the hints you need to solve the game’s puzzles and progress.

It’s a simple premise, but its execution is complex. There are a couple of Rosetta stones in the game, but most symbols must be decoded from the selection of contexts in which they appear. This can sometimes be quite difficult, since the semantics of the languages can get complicated in surprisingly realistic ways. Different real-life languages do not all have terms for the exact same concepts, and the same holds true for the languages in Sennaar. It’s easy to assume that a symbol means ‘jar’ when the actual meaning is the broader term ‘container’; or to guess ‘follow’ when the real meaning is ‘catch’. To make things a little easier, you have access to a virtual notebook full of drawings portraying the meanings of the different words. At any given time, you can place a word (that is to say, one of the symbols which represents words) next to a drawing, and if you find the right words for all the drawings on a page, the notebook will confirm them and give you the official translation of the word in whichever language you play the game. The notebook is a great help in translating the languages without making it all too easy, since many of the words have abstract meanings which are difficult to recognise from drawings alone.

Before I continue, I should clarify a few things: The languages in Sennaar exist exclusively in written form. The games’ characters speak only in low mumbles with no consistent grammar, accompanied by text in their respective invented scripts. Still, it’s clear that their languages aren’t just English or French, as the different scripts have specific traits that mirror particular grammatical features in real spoken languages. And since I want to discuss some of these traits in the following, this is the point where I recommend anyone with an interest in playing the game for themselves to stop reading until you’ve played it yourself. If you have a passing interest in conlangs and video games (which I assume you must if you’ve read even this far), this game is worth experiencing without prior knowledge, and in the following I will be discussing the grammars of the languages and the plot of the game – you’ve been warned!

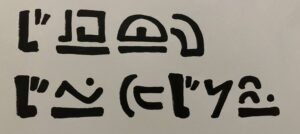

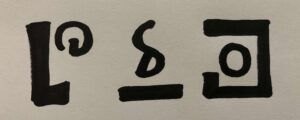

Chants of Sennaar contains five written languages, and all of them are made of ideograms, which means that each of their symbols represents a concept or an idea rather than a spoken word. In written English, which is not made of ideograms, written words like ‘tower’ are made of letters, which represent sounds (not on a 1:1 basis, but close enough to work) to form the spoken word ‘tower’, which in turn represents the idea of a tower. In that way, the journey from written symbol to meaning passes through a spoken form – but this isn’t the case for Sennaar’s scripts.

Since the game is only about 9-12 hours long and contains five different languages, none of them have a very big vocabulary. But several of them have systematic features that make it possible to create new signs that would be understood by other players. The best example of this is the first language, which in the game is called “the Devotees’ language”. Once you’ve guessed the translations of enough different symbols, you begin to notice the visual similarities in some of the symbols, and the connections between the meanings of those signs. For example, there’s a vertical line with a small foot that appears in the symbols for ‘you’, ‘I’, ‘warrior’ and ‘preacher’. But that line can also stand as a symbol on its own, and in that case, it simply means ‘human’. Once you recognise the pattern, you can connect the line with other elements in the Devotees’ language to create new signs with the meaning ‘human with a relation to X’, without the game having shown such a symbol to you. For example, I know what the Devotees’ symbol for ‘musician’ must look like, even though that never appears in the game: It’s the symbols for ‘human’ and ‘music’, put together in the conventional way. This is one of the areas where Sennaar’s languages draw inspiration from the real world, as this basic idea is the same as that of the radicals which make up Chinese writing.

The recurring elements can carry both semantic and grammatical meaning: Just as certain parts of the symbols can mean ‘human’ or ‘place’, there are other parts that signify things like whether a word is a verb. If you enjoy discovering systems, it’s an immensely satisfying experience to gradually teach yourself how to put together your own symbols.

Still, the game developers’ love of languages doesn’t truly reveal itself until you compare the different languages – which is something the game itself prompts you to do, since some of the puzzles involve translating from one language to another. In this way, the player’s attention is directed to their typological differences. The Devotees’ language uses reduplication (which is a fancy grammar term for ‘repetition’) to form plural nouns, whereas the Warriors’ language have a dedicated symbol for that purpose. The variation reflects linguistic diversity as seen in real languages, which should be enough to warm any linguist’s heart just a little bit.

Speaking strictly as a linguist, I could criticise the game for the limits of its linguistic variation. Four of its five languages follow the Subject-Verb-Object word order, which isn’t even the most common word order in real languages (although it is the one that most English speakers are most familiar with from Indo-European languages). And sure, it would have been fun for me if the languages had been a bit more typologically varied, but the game also has to be enjoyable without a degree in linguistics, and I think the level of variety that the game offers already shows an admirable dedication to creating believable and interesting scripts.

I have personally completed one playthrough of the game, and have since then looked over the shoulders of two other groups playing through the first section. The first group consisted of a couple of friends who are also trained linguists, and the second was my family. Surprisingly, it was my family who decided to up the difficulty by making do without the in-game notebook. This meant that they never got confirmation whether their translations were right or wrong, so they were far more dependent on context to complete the game’s challenges. It was obvious how this made the game a whole lot tougher, but in hindsight, it’s a little bit melancholy to think that, having already decoded the languages and solved the puzzles, I won’t be able to try the game with that self-imposed extra challenge myself. The experience seemed frustrating at times, but also created a more organic experience of gathering and analysing linguistic data. That being said, unless pure challenge is the main selling point of a game for you, using the notebook as intended is probably how you’ll get the most fun out of this.

Chants of Sennaar is, so to speak, taken up a level when you compare the game mechanics, i.e. various translation tasks, with the narrative, i.e. the game’s story. The final goal is to reunite the five peoples living in the tower by translating their attempts at communication with each other, thereby opening doors and building bridges between the different levels (metaphorically and literally). The basic building blocks are blatantly borrowed from Babel: There’s a tower, there’s religious motifs, and there’s a confusion of languages leading to division between different peoples. But this time, the story plays out in reverse: The five peoples aren’t robbed of their ability to communicate, but gradually find it over the course of the game, and are thereby enabled to reach new heights (again, this is both in a metaphorical and a literal sense; the game doesn’t aim for subtlety). The message I take away from it is that we do not all need to speak the same language to get along and cooperate – as long as we bother to understand the languages of others.

Chants of Sennaar uses languages in a way that I haven’t seen in any other game, and tells a story about linguistic variety and the importance of translators and interpreters. Next week, I’ll be discussing a game which uses conlanging in a slightly different, but also very interesting way: Heaven’s Vault from the English studio Inkle.

Gustav Styrbjørn Johannessen has a Master’s degree in Linguistics from Aarhus University. His education has taught him a lot about language and, through the indirect method known as procrastinating on homework, also about video games.

2 thoughts on “Conlangs & computer games, part 2: The reconstruction of Babel”