As linguists, we investigate all sorts of building bocks of language, such as sentences, predicates, prefixes and suffixes, and even individual sounds like p and z. Most of these building blocks have some kind of meaning. For example, a sentence like The cat sat on the mat means something, a predicate like is crazy in John is crazy means something, and even prefixes and suffixes mean something, such as pre- in pre-heated, which means something like ‘done in advance’, so that pre-heated means ‘heated in advance’. But, you may ask, do sounds like p and z also have meaning?

We know that sounds may distinguish meaning, but it is not so obvious that they have meaning. For example, the words cat and mat are distinguished by a single sound, /k/ for cat and /m/ for mat. But it is not like the /k/ sound in cat (written c) means something “catty”, and the /m/ in mat means something “matty”— most words with /k/ don’t have anything to do with cats at all. In linguistics, we call such sounds, which do not have meaning but which can distinguish between meanings, phonemes.

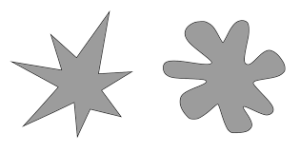

But the story does not end there (this would be a very short blog post if it did!). For example, some studies have shown that people associate ‘sharper’ sounds with objects that have jagged shapes, and ‘rounder’ sounds with objects that have rounded shapes. We call this the Bouba-Kiki effect; for example, if you make people choose between the names Bouba (which has round sounds) and Kiki (which has sharp sounds) for the two shapes in the picture below, most people would call the shape on the left a Kiki and the one on the right a Bouba.

What the Bouba-Kiki effect shows is that certain types of sounds may be associated with certain types of things. Findings from other studies suggest similar things; for example, words with a high vowel like /i/ as in tweet are more often associated with small things (mini, peepee), while words with low vowels like /a/ and /o/ are more often associated with larger things. This suggests that sounds can in fact have meaning. But of course neither Bouba nor Kiki are real words in English, so you might wonder if we can find examples of sounds with meaning in actual words. The answer is yes, and we don’t even have to look at exotic languages to find them.

For example, if you look at all the English words that start with fl-, you’ll see that many of those words have a certain meaning along the lines of ‘moving light’, such as in flash, flame, flicker, etc. Similarly, words that begin with gl- often mean something like ‘vision’, such as glance or glare, or ‘light’ such as glow, gleam or glisten.

So what are gl- and fl- exactly? Are they prefixes? Well, a prefix like pre- in pre-heated can usually be left out (heated) or swapped for another prefix like over- (over-heated). But we cannot take fl- away from flicker, because -icker does not mean anything, so fl- is not a prefix but simply a sound. On the other hand, fl- does mean something, namely ‘moving light’, so it is a sound with meaning. In linguistics we call such meaning-bearing sounds phonaesthemes, and they probably occur in all languages.

Interesting as that may sound, things get even more interesting when we look at phonaesthemes in West-Flemish. This is a dialect of Dutch spoken in Flanders, Belgium (Joost’s mother tongue, but—despite being a Dutch speaker—about as intelligible as Klingon to Jeroen). West-Flemish has the phonaesthemes tj- and dj- (pronounced /ʧ/ as in chip and /ʤ/ as in jelly), both of which have a variety of meanings like ‘small’, ‘insignificant’ and ‘helpless’, but also ‘dirty’ or ‘vulgar’. If you open up any West-Flemish dictionary, you’ll see that there are many words that start with tj- and dj-, and that most of them indeed have such meanings.

To give you some examples (we assume you don’t have a West-Flemish dictionary handy), words like tjikken and tjiepen have to do with smallness and are used for the singing of small birds, like finches, and words like tjakken and tjaffen have to do with helplessness and mean something like ‘stumble, trip’ or ‘walk with a limp’.

Many words having to do with low-status or dirty things also start with tj- and dj- and like tjeute ‘pig’, tjul ‘dork, simpleton’, and even some vulgar words like tjingel, which means ‘penis’ or ‘prick’.

What is more, such tj- and dj-words can be derived from other words that start with a different sound. For example, the vulgar word tjingel ‘penis’ comes from tingel, which means ‘thorn’ or ‘stinger’, and tjul ‘dork, simpleton’ comes from sul, which means the same thing but is not as vulgar-sounding as tjul. Further, the ‘helpless’ word tjeuvelen, which means ‘to stumble’ or ‘to fall over’ comes from schuiven, which simply means ‘to slide’, and the ‘small’ word tjoepke, which means ‘small cap, tip’ comes from topke, which means ‘cap’ or ‘top’ and is not as small as a tjoepke.

As you might have guessed, we don’t have this in English—in fact, almost no language has it. Just imagine, if we would have the same in English, we could maybe change top to tjop, which would mean a small top, or maybe we could change a word like sucker to tjucker to create a more vulgar swearword. Because it’s such a rare phenomenon, we decided to find out how this came about in West-Flemish. The answer might surprise you: centuries ago, the West-Flemish were imitating speakers of another language called Picard. And not in a nice way—they were actually making fun of them.

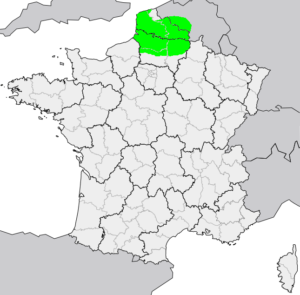

Picard is a dialect of French spoken in northern France and southern Belgium—right next to where West-Flemish is spoken. If you’ve seen the film Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis, you’ll have heard some Picard, and you may have noticed that it sounds very different from French. One of the things that’s so different about Picard is that—you guessed it—many words start with tj- or dj-. For example, the French word quand ‘when’ is pronounced as [ʧɑ̃] in Picard, and the word quinze ‘fifteen’ as [ʧɛ̃s]. It will probably come as no surprise that the French are not exactly fans of this pronunciation, but it is looked down upon in the Flemish-speaking regions of Belgium as well.

What is more, Picard speakers started entering the West-Flemish speaking regions for trade around the 11th century, an influx that persisted for hundred of years, forcing the West-Flemish community to learn Picard in order to trade with them. Not everybody liked these newcomers, however, and people mockingly started creating ‘Picard-style’ words that symbolised their negative attitude towards these new neighbours, resulting in exactly the types of meaning we still see in tj- and dj-words today.

Jeroen Willemsen and Joost Roger Robbe both work at Aarhus University in Denmark.

Jeroen Willemsen is a theoretical and descriptive linguist working on a description of a Papuan language called Reta.

Joost Robbe is a historical linguist researching a dead dialect of Dutch as spoken in Amager, Denmark.

They bundled their forces to present to you this tjerribly interesting phenomenon.