Cefas van Rossem defended his thesis on the now extinct Dutch Creole language of the former Danish Antilles, or Dansk Vestindien ‘the Danish West Indies’, or the Virgin Islands, on December 20 2017, at the Radboud University of Nijmegen. I had the privilege of judging the manuscript and being one of the eight (!) opponents.

It is in fact the second dissertation on the language within a year – accidentally one hundred years after the three islands St John, St. Croix and St. Thomas were sold by Denmark to the USA. Robbert van Sluijs defended his thesis of the development of tense, mood and aspect in the language in May 2017.

Why would a Danish colony foster a creole with Dutch as its lexifier?

The Danes were not very successful colonists, in the sense that it was difficult to persuade Danes to move to tropical areas. When the Danes almost accidentally had claimed a small part of India, they felt they should colonize it and save the souls of the locals, but they could not find Danish missionaries looking for an adventure. Therefore the Danes advertised the job in Germany, successfully, and then Denmark sent German missionaries like Ziegenbalg to India, after making them Danish citizens. In the Danish Antilles, it was quite similar. Danes were not enthusiastic about moving there. Perhaps for good reasons: the first generation of Danes who moved to the Antilles all died within a short time, succumbing to tropical illnesses. That is not very attractive. It is a polite death sentence. Therefore the islands were populated predominantly by settlers not from Denmark. The immigrants came not only from Europe, but also from other Caribbean islands. And speakers of Dutch were apparently prominent among them. Not only Europeans, but also enslaved Africans. In 1688, sixteen years after the permanent settlement of St. Thomas, 45 % of the colonists came from the Netherlands and Flanders, and 13 % from Denmark. And people came also from other Dutch colonies, like St. Eustatius. No wonder that a Dutch creole emerged on the islands.

In the early 17th century, a new pietistic religious movement spread through Europe. They were called Moravian Brethren (after the region of emergence), Herrnhutters (after their main settlement in Herrnhut, Germany, close to the Czech border) or Evangelische Brüdergemeinde, as they call themselves. It was a movement of strong faith, commitment to the community, equality of women and men, and egalitarian. When the convert Duke of Zinzendorf met an enslaved boy Anton Ulrich from the Virgin Islands in Copenhagen in 1731, he became convinced that the slaves in the Danish Antilles needed Christian supervision, and a few years later, manual workers from Germany left for the islands to provide spiritual Christian guidance to the enslaved population. And they decided to use the vernacular of the island rather than Dutch, German or Danish: the Dutch-lexifier creole language.

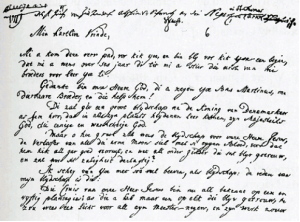

Min hartlive Vrinde,

my heart-loved friend.PL

Mi a kom deze verr pad, vor kik yoe,

1SG PST come DEM far path FOR see 2PL

en bin bly vor kik een begin, dat mi a

and BE happy FOR see a beginning that 1SG PST

wens over ses jaar di tit mi a Stier die eerste

wish over six year DET time 1SG PST send DET first

van mi broeders voor leer yoe -Li.

of 1SG brother.PL FOR teach 2PL

Gedankt bin onze Heere God, di a zegen

thanked BE our Lord God DET PST bless

yoe Bas Martinus, mi dierbaare Broeder, en die help hem!

2PL BAAS Martinus 1SG dear brother and DET help 3SG

Di zal giv een groot blydschap na de Koning

DET will give a great happiness NA DET king

The Moravian Brethren have been called “the first creolists”, as they painstakingly documented the creole languages of the Dutch West Indies (the Dutch-lexifier creole) and Suriname (at least two English-lexifier creoles). For the Danish West Indies, this means that the creole has been documented for a staggering 250 years. In 1996, a book was published with an anthology of texts, by the author of the dissertation discussed here and his colleague Hein van der Voort, who now devotes his life to the documentation of Brazilian indigenous languages.

More than 20 years later, Cefas van Rossem produced this remarkable dissertation, based on documents in the language, most of them produced by the Moravian Brethren. He is trained as a Dutch philologist, which is clear because of his careful editorial work of the manuscripts. He has transcribed and studied parts of the huge body of texts in the creole language, and compared different versions. He has also painstakingly noted all changes and corrections in the manuscript texts, including subsequent versions. As far as I know, this has never been done before for any texts in creole languages. He deals not only with older Moravian manuscripts, but also with the notes made by the American Scandinavianist Frank Nelson in 1936, who was on holiday on St. Croix, and who did fieldwork on the Dutch creole. Van Rossem corresponded with him in 1996. His chapter about the quest for Nelson’s fieldnotes reads like a detective story. An interesting component to the story of Nelson’s field notes is that researchers before him had focused on the creole as found in St. Thomas and St. John. Little data had been collected from St. Croix prior to Nelson’s efforts, as the Dutch-based creole was less prominent on that island. English and an English-lexifier creole dominated.

The philological background of the author is an asset, but it also has its drawbacks, in that the Nelson material is presented exactly as it was elicited, but it would have been more useful to present it in alphabetical order or in semantic groupings (e.g. body parts, kinship, food) in my view.

Van Rossem looks at the material also from the perspective of audience design, a model for spoken language developed by Alan Bell, who distinguishes the author/speaker, and then addressees, auditors, overhearers and eavesdroppers, in addition to a referee who is not present, but may influence the way people speak, e.g. a British schoolmaster who has taught his pupils to never split infinitives. Cefas van Rossem does a courageous attempt to apply the model to written languages, but in my view he misses a number of overhearers and eavesdroppers, including Moravians in other parts of the world, printers, and perhaps even (future) researchers like himself.

Despite these critical remarks, the book is a great achievement, and a welcome addition to the literature on creole languages, on the history of the Danish West Indies, on philology and on the evolution of newly born languages.

Cefas van Rossem, by the way, has been keeping a very interesting blog on Virgin Islands Dutch Creole, mostly in English in order to inform the international scientific community. We hope very much that he will continue with this.

The Dutch-lexifier creole went extinct in 1987, when Alice Stevens, the last speaker, died. The language has been replaced on the island by an English-lexifier Creole language and by English. The English creole on the island of Saint Croix is now a threatened language as well. Van Rossem has unearthed a number of interesting metalinguistic comments from concerning the early history of this creole, too. The linguist Arnold Highfield is working to finish a monumental dictionary of the language, and Kristoffer Friis Bøegh is writing his dissertation on the grammar and history of the language at Aarhus University. You can read about his fieldwork here, about local proverbs and on Danish loans in Saint Croix creole (both written in Danish).

The book:

Cefas van Rossem. 2017. The Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Textual Heritage: Philological Perspectives on Authenticity and Audience Design.

Utrecht: LOT. LOT Number: 477

ISBN: 978-94-6093-261-8

451 pages.

Peter Bakker is a creolist and linguist working at Aarhus University.

This (Language Death) is one of the very neglected areas of Creole Studies. the work sparks new interests in and motivation to explore the historical and social factors that underpin much of Creole linguistics. Congratulations

Thank you so much!