Today is International Day of the Basque Language, which we celebrate at Lingoblog with an article by Iván Igartua.

Being a language isolate in Europe is a strenuous condition, often fraught with vicissitudes. There are over 150 genetically isolated languages in the world (for which no relatives have been found thus far), but I would venture that none of them has inspired so many hypotheses of all sorts about its remote origin and possible genetic connections as the Basque language. Albeit thoroughly unconvincingly, Basque has been alternately related to Etruscan, Burushaski, Pictish, Chinese, the Celtic group of Indo-European languages, the Berber and Caucasian languages, the Na-Dene linguistic phylum, or the Uralic and Paleo-Siberian languages, among many others. Some otherwise serious linguists claim to have identified traces of Basque (or the so-called Vasconic) in different places of Europe and have even suggested Basque etymologies for toponyms like Munich (Germ. München) and Ebersberg. What some paleolinguists used to know as Old European would actually have been, following these speculations, a language more or less closely related to Basque. One of the more recent kinship hypotheses tries to connect Proto-Basque (that is, an unattested, reconstructed form of Basque) with Proto-Indo-European on the basis of several allegedly common ancient traits. But all this remains highly controversial.

Basque and Iberian

More reasonable approaches situate Basque (more precisely, its ancestors) within the realm of the languages spoken in the Iberian Peninsula as well as north of the Pyrenees in the antiquity.

In eastern regions of modern Spain and in southeastern France, a language called Iberian was spoken at that time. The linguistic testimony spans a period from the late fifth century BCE to the first century CE. Iberian inscriptions have been found mainly along the Mediterranean coast of the peninsula. They were written using a special type of script, defined as a semi-syllabary, which combines elements of alphabets, representing individual sounds, and syllabaries, representing whole (open) syllables. It is not inconceivable that in pre-Roman times Basque was in contact with Iberian dialects. Several similarities between the two languages, both in phonology and grammar, can be due to a long-term, intense history of contact. Neither Basque (at older stages of development) nor Iberian appears to have made extensive use of sounds like /p/ and /m/, and both communities were reluctant to pronounce rhotics at the beginning of a word. Regarding grammar, Basque displays ergative marking on agents (in other words, it distinguishes active from inactive subjects) and Iberian was also probably characterized by this type of morphosyntactic alignment. A few verbal forms certainly seem to be similar (ekiar in Iberian, ekien in Vasconic, zegien ‘(s)he did’ in Basque) both in form and function. Furthermore, according to some authors, the numeral system was nearly the same (Iberian ban, Basque bat ‘one’, Iberian bi(n), Basque bi ‘two’, Iberian irur, Basque hirur ‘three’, Iberian bors(te), Basque bost/bortz ‘five’, etc.), even though we are not fully certain as to the real value of those Iberian words (if not just sequences).

All these shared characteristics may have different explanations: while, based on such properties, some people have hastened to proclaim the genetic relationship between Iberian and Basque, others consider them to be at best a consequence of the prolonged contact between the two linguistic communities. The degree of structural convergence would be consistent with the idea of a typological area that took centuries to become consolidated. In this view, Iberian and Basque are not to be seen as members of the same linguistic family, although, as the great Bascologist Luis Michelena (Koldo Mitxelena, in Basque spelling) once said, “there is still a whole series of coincidences –formal, external, it is true, since the meaning is not accessible to us– that oblige us not to abandon the idea that there may be some kind of kinship”. The point is, accordingly, to define and demonstrate what kind of relationship linked the two languages, but there is currently no consensus on this disputed issue.

What we know without a shadow of a doubt is that Basque has proven useless in trying to make sense of the Iberian texts, which can be read but not understood, as pointed out by Michelena. This is a serious obstacle to the idea of a Basque-Iberian kinship. Of course, there is a whole troop of linguistic dilettantes that still believe that Iberian inscriptions are translatable with the aid of Basque. Such attempts have absolutely nothing to do with professional linguistics. They are not even worthy of attention.

Basque and Aquitanian

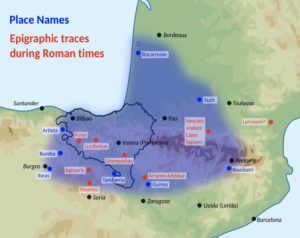

The only sound, unequivocal genetic connection that can be sustained is that linking Basque and Aquitanian (or Aquitanian-Vasconic), the indigenous language reflected in some Roman inscriptions dating back to between the first and third centuries CE.

These ancient texts include anthroponyms and theonyms, some of which are formally and semantically really close to their modern Basque counterparts. A quick glance at these parallels is all it takes: the Aquitanian (and Vasconic) nouns Cison/Cisson, Sembe, Nescato and Ombe or Umme can readily be associated with Basque gizon ‘man’, seme ‘son’, neska ‘girl’ and ume ‘child’.

There are certainly more difficulties with other old names, for which no Basque equivalents can be easily found. Some grammatical elements appear to be identical, like the suffix –t(h)ar, meaning origin or appurtenance. But, maybe more importantly, what makes Aquitanian-Vasconic and Basque especially akin (and different from surrounding languages) is the presence of the sound /h/, an aspiration that is lacking in the other Paleohispanic languages, whether Iberian, Celtiberian, or Latin. This sound, which is still preserved in Eastern Basque varieties, is conveniently represented by the aitch in the Roman inscriptions of Aquitania and Hispania that contain indigenous names. The presence of the aitch amounts to a proof of Basqueness. As mentioned, there is no trace of this kind of sound in Iberian.

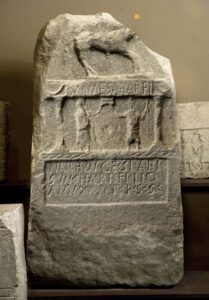

A hand with an inscription

In June of 2021, an exceptional inscription written on a bronze hand was unearthed in Aranguren, Navarre, inside the territory formerly inhabited by the Vascones.

It was presented officially to the general public by the end of 2022 and the canonical description of the piece and its content has been given in a recent paper in the journal Antiquity (2024).

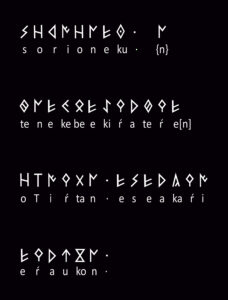

It has come to be known as the Hand of Irulegi, dating to the first century BCE and written in a local version of the Iberian script. The first analyses pointed to Vasconic (the equivalent of Aquitanian south of the Pyrenees) as the language probably underlying the inscription, all the more so when the first word of the inscription was read as sorioneku (or sorioneke), which appears to be extremely close to the Basque word zorioneko ‘fortunate, lucky’, an adjectival formation involving zori ‘fate’ and (h)on ‘good’ plus a suffix –(e)ko.

But then the initial enthusiasm waned at the sight of the following lines of the inscription, in which the linguistic distance with respect to any known word or construction in Basque turned out to be desperately big. Only a few sequences can be more or less reliably matched with recognizable Basque elements, as in the case of the last word eŕaukon, which reminds us of Basque verbal forms such as zeraukon ‘(s)he gave’. The comparison with Iberian has not yielded great results either. If this inscription was truly written in Vasconic, we have to concede that this likely ancestor of Basque, spoken some 2,000 years ago, was really quite different from the modern language, which is not particularly striking in itself, given the time lapse. The real problem is that the language of the Hand of Irulegi happens to be different to the point that it gives us almost no clues to interpret and understand the text. This is undeniably more worrisome and casts severe doubts on the linguistic position (and eventually affiliation) of the inscription. Be that as it may, if we are still tempted to regard Basque as a window into the linguistic and cultural past of the Iberian Peninsula (which can, no doubt, make perfect sense under certain circumstances), we must acknowledge that it is, at best, an imperfect window that can only offer a partial and, any way one looks at it, incomplete view of the situation there in ancient times.

Further reading

Aiestaran et al. 2024. A Vasconic inscription on a bronze hand: writing and rituality in the Iron Age. Irulegi settlement (Ebro Valley). Antiquity 98 (367). 66–84.

Bakker, Peter. 2020. Review of Blevins 2018. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 52. 563–594.

Blevins, Juliette. 2018. Advances in Proto-Basque Reconstruction with Evidence for the Proto-Indo-European-Euskarian Hypothesis. London: Routledge.

De Hoz, Javier. 2001. Hacia una tipología del ibérico. In Francisco Villar & M.ª Pilar Fernández Álvarez (eds.), Religión, lengua y cultura prerromanas de Hispania, 334–362. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca.

Gorrochategui, Joaquín. 1984, Onomástica indígena de Aquitania. Bilbao: University of the Basque Country Press.

Gorrochategui, Joaquín. 2020. Aquitanian-Vasconic. Zaragoza: University of Zaragoza Press.

Gorrochategui, Joaquín. 2022. The relationship between Aquitanian and Basque: achievements and challenges of the comparative method in a context of poor documentation. In Thiago Acosta Chacon, Nala H. Lee & W. D. L. Silva (eds.), Language Change and Linguistic Diversity. Studies in Honour of Lyle Campbell, 105–129. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Gorrochategui, Joaquín, Iván Igartua & Joseba A. Lakarra (eds.). 2018. Historia de la lengua vasca / Euskararen historia. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Basque Government.

Igartua, Iván & Xabier Zabaltza. 2021. Euskara – The Basque Language. Donostia-San Sebastián: Etxepare Institute of Basque Language and Culture.

Kitson, Peter R. 1996. British and European river names. Transactions of the Philological Society 94 (2). 73–118.

Michelena, Luis. 1964. Sobre el pasado de la lengua vasca. San Sebastián: Auñamendi (= Obras completas, V, 2011, 1–115).

Michelena, Luis. 1977. La lengua vasca. Durango: Leopoldo Zugaza (= Obras completas, IV, 2011, 13–66).

Moncunill, Noemí & Javier Velaza. 2020. Iberian. Palaeohispanica 20. 591–629.

Trask, R. L. 1997. The History of Basque. London: Routledge.

Vennemann, Theo. 2003. Europa Vasconica – Europa Semitica. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Iván Igartua is Professor of Slavic Philology at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). He has studied some aspects of the historical phonology and morphology of Basque. He is co-author of Euskara – The Basque Language (Etxepare, 2021) and co-editor of Historia de la lengua vasca (Basque Government, 2018) and Basque. Language Minorities in Europe (De Gruyter, 2020).