Many linguists are interested in linguistic deficits (i.e. aphasia) that arise after brain injury. By investigating them, we can potentially infer something about how language is organised in people without brain damage – both which components comprise language and where the different components are located in the brain. We hope to answer questions like: Is there a difference between grammar and lexicon? Are language comprehension and language production located in different brain areas? How do we access the meanings of words, and are words with similar meanings also close to each other in the brain? The problem with a lot of research on aphasia, however, is that it has primarily focused on European languages that are structurally very similar.

This article is about an investigation by me and my colleagues of a radically different language, namely West Greenlandic or Kalaallisut. The project emerged out of pure curiosity; no one had previously researched how aphasia would affect a language such as West Greenlandic where both morphology and syntax are very different from that of well-known European languages.

What can aphasia tell us about language in the brain?

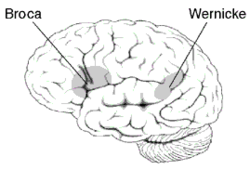

Aphasia has long fascinated linguists and has, perhaps most famously, given rise to classical theories about grammar having its primary location in a specific area in the left frontal lobe (Broca’s area), while lexicon – i.e. vocabulary – is primarily thought to be located somewhere in the temporal lobe (Wernicke’s area). Patients with lesions following cerebral thrombosis or brain hemorrhage in Broca’s area have difficulties producing fluent speech and have a tendency to speak in a telegraphic manner characterised by a predominance of content words and few or no grammatical elements. However, they typically understand most of what is said to them unless the meaning is tied to unusual grammatical constructions. On the other hand, patients with lesions in Wernicke’s area generally produce fluent speech that is grammatically coherent but mostly incoherent when it comes to meaning. They also have more difficulties with understanding what is said to them. Theories like these are appealing because they allow us to say ‘this is where grammar is located’ and ‘this is where the mental lexicon is located’ but they are likely too simple to be true. Recent studies called into question the simple distinctions between both the grammar and lexicon and between comprehension and production. In the most comprehensive cross-linguistic work on agrammatic, non-fluent aphasia to date (Menn & Obler, 1990), the authors outline a much looser definition of aphasia. They characterise agrammatic speech as slow with short sentences and short phrases – in addition, there is often some “limited use” of syntactic and morphological tools. Since precisely syntax and morphology are somewhat unwieldy and fuzzy concepts in West Greenlandic, this language makes an especially interesting case for studying aphasia.

Affix upon affix upon affix

Most people probably know that West Greenlandic is a language characterised by extremely long words – there is actually no limit as to how many morphemes can be strung together in West Greenlandic. Something that would require a whole sentence in English is often expressed with a single word. For example, aalassarlussiartupallattupilussuuvunga means ’My ability to move around became gradually (but tremendously) worse and worse’ (a one-word sentence uttered by one of the control participants in our study). A thorough examination of West Greenlandic morphology is far beyond the scope of what we can go through here but I will outline the most important aspects. West Greenlandic grammar is traditionally divided into external and internal morphology (roughly syntax and morphology, respectively). Most words consist of a stem followed by several derivational affixes that can be inserted between the stem and an inflectional suffix. Around 400 of these derivational affixes are used productively in modern West Greenlandic and they fall into four broad categories:

- verbal modifiers that function in roughly the same way as adverbs do in English (e.g. –pilussu- ‘powerful’, which can be added to the verb stem anorler – ‘it is windy (literally: ‘it is winding’)’ to produce ‘it is extremely windy’),

- nominal modifiers (e.g. –suaq– ‘big’ which can be added to the verb stem anori ‘wind’ to create the word anorersuaq ‘storm’),

- verbalisers which transform nominal stems into verb stems (e.g. –qar ‘to have x’, which can be added to the plural of suluk ‘wing’ and thus become suloqarpoq ‘has/have wings’), and

- nominalisers which transform verbal stems into nominal stems (e.g. –vik ‘place/time where the action takes place’ which is added to allappoq ‘writing’ and becomes allaffik ‘desk’).

Furthermore, there are more than 300 inflectional suffixes organised in verbal and nominal paradigms. Thus, the internal syntax – i.e. the morphology – is notably complex. The external syntax – i.e. what we would normally refer to as syntax – is on the other hand relatively simple. The most complex processes happen when one sentence is subordinate to another (which can often be seen in the mood of the verb), when the sentence has both a subject and an object, or when the number of arguments the verb has changes due to a valence-changing suffix. Valence refers to how many arguments a verb requires for the sentence to be grammatically correct – for example, the verb is monovalent if it only requires a subject (‘she sleeps’), and it is divalent if the verb requires both an object and a subject (‘she eats apples’). In West Greenlandic, there are two types of affixes that increase the valence (causative and applicative), thus making the verbs require more arguments, and two types of affixes that decrease the valence (passive and anti-passive), making the verbs require less arguments. Imagine the sentence ‘she eats the apple’ where the verb has two arguments – in English, we can decrease the valence with a passive form (‘the apple is eaten by her’) where focus is shifted away from the former subject which in fact becomes unnecessary (‘the apple is eaten’ is also grammatically correct).

We were not sure how aphasia would be expressed in a polysynthetic language like West Greenlandic, especially with the distinction between grammar and lexicon being much less clear than in languages like English and Danish. We expected that the morphology would be affected because of its complexity – perhaps that the participants with aphasia would produce simpler sentences and stems without inflectional endings the same way we see it in agrammatic aphasia in English and other related languages. If the participants who had aphasia used long words, we expected to at least see less variation in the affixes – perhaps only the most common, fixed constructions. Perhaps inflectional affixes would disappear whereas derivational affixes would remain since the latter can be thought of as less ‘grammatical’ in nature. We studied five participants with aphasia and five control participants who were matched in terms of age, gender, dialect, and education.

Intact morphology – damaged syntax

Our findings were surprising. The speech of the participants with aphasia did not seem to be any less morphologically complex than that of the control participants! They produced just as many morphemes per word and there was no difference in neither the amount nor the range of any of the different types of affixes. The participants with aphasia did not produce more grammatical mistakes either. They did, however, speak at a significantly lower pace and used shorter phrases. The differences seemed to lie in the external syntax: The participants with aphasia used fewer transitive verbs, fewer subordinating verb forms and fewer valence-changing verb forms. What do these results mean for aphasia studies and linguistic theories in general? I would argue that we need to stop relying solely on European languages – especially English – as a foundation for linguistic theories. This simply will not do when we have upwards of 6000 languages in the world, most of which have a radically different structure. Our West Greenlandic study casts doubt on traditional grammar/lexicon theory in aphasia research where some patients have grammatical deficits and other have lexical deficits. Our results instead support a more functional explanation relying on a “communicative burden” conception where the parts of language that are most necessary for communication also are the best preserved. Inflectional affixes in English, for example, do not carry as much of the communicative burden since the meaning can often be inferred from word order. This cannot be done in West Greenlandic which might mean that the morphology is more robust. Other studies of aphasia in languages with high morphological complexity (e.g. Japanese, Turkish, and Finnish) show similar patterns. As with other aphasia studies, ours is of course limited by the very small segment of patients which we tried to counteract with our group of matched control participants.

Johanne Nedergård has studied psychology, linguistics, philosophy, and cognitive science at the University of Oxford and the University of Edinburgh and has, among other things, researched Danish and West Greenlandic aphasia and the role of perspective-taking in communication. She is currently employed as a PhD student at the Institute for Communication and Culture at Aarhus University, where she studies the role of the inner voice in control of behaviour.

This post was translated from Danish by Hannah Fedder Williams and Johanne Nedegård.