Shetland is the northernmost part of the UK, an archipelago straddling the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the North Sea to the east between Scotland, Norway and Faroe. The strategic location, smack in the middle of maritime trade and migration routes, means that the islands have been a place of contact for centuries, if not millennia.

Shetland has been inhabited for at least 6,000 years: the earliest evidence of human settlement in Shetland is the shell midden of West Voe dated 4200-3600 BC. These settlers were hunter-gatherers/fishers, but we don’t know when they came to Shetland or from where .

At some point around 3700-3600 BC we see evidence of a farming lifestyle in West Voe, for example that cattle, sheep and goat bones now start appearing in the middens. The tombs, tools and pottery show similarities with those in western Scotland, but not with those in Orkney and Caithness. It therefore looks like these neolithic farmers came to Shetland directly from the western Scottish mainland and not via Orkney. They probably came in waves rather than in one big colonising settlement. It was these settlers who brought the kye (cattle) and the sheep to Shetland which are the ancestors of the current native Shetland breeds of kye and sheep. The horse would only start appearing in Shetland some 1,000-1,500 years later.

Fast forward some 4,000 years to 4-500 AD. By now the entire British and Irish mainlands are settled by speakers of various Celtic languages. In the north of Scotland we have the Picts. At around 4-500 AD, possibly even as early as around 300 AD, the Picts settle in Shetland. At the same time the remaining Roman troops in Britain move out and mercenaries speaking varieties of the North Sea Germanic languages migrate to Britain. They settled in different areas of the British mainland: the Jutes settled in what is now Kent; the Frisians settled just north of that; the Saxons settled in what is now south-central and south-western England; and the Angles settled in two large areas: Mercia, which is now central and eastern England, and Northumbria, which is now northern England and southern Scotland. It was Mercian Old English that would eventually develop into what we now call English, while it was Northumbrian Old English that would develop into what we now call Scots. Two very closely related languages, made closer by intense contact, but each of them distinct and neither of them a dialect of the other.

In the late 8th century the Norse expansion started. Shetland was first settled by speakers of Western Norse around 790. We don’t know exactly what happened with the Pictish population that was already living in Shetland at the time. Very little remains of their language: the three place names Yell, Unst and Fetlar are thought to be pre-Norse, but other than that there are hardly any linguistic traces of the previous population.

In 875 Harald Hårfagre claimed the archipelagos of Shetland and Orkney, as well as Caithness on the northern Scottish mainland. Kirkwall became the seat of the earldom. With this, Western Norse was established on the island, and would evolve to Norn. It would remain in Shetland for nearly 1,000 years, with the last speaker (or possibly rememberer), Walter Sutherland of Skaw in Unst at the northern tip of Shetland, passing away in 1850.

Starting around the late 14th century or early 15th century, contact with Scotland grew and more Scots speakers migrated to Shetland. These were mainly tradesmen, clergy, craftsmen, and so on. At the same time the Hanseatic Trade was in full swing, and Shetland was within that trading sphere. Shortly after that, the Dutch herring trade would also start in a large scale. With this, speakers of both Scots and the Low German languages were in constant and intense contact with the Shetlanders, to the extent that contemporary testimonies write about the ease with which Shetlanders communicated in ‘Gothic’ (Norn), Scots, and ‘Dutch’ (meaning either Low German or Dutch).

In 1469 Shetland was pawned by Christian I of Denmark (because by now Norway and Denmark was under the Danish crown) to James III of Scotland as part of the dowry for his daughter Margareta. Orkney had been pawned in 1468. With this the Scots influence steadily grows and the sociopolitically powerful language shifts from Norn to Scots. However, Shetland remained bilingual for another 250 years. Data for Norn, especially longitudinal data, is extremely scanty. But from what little evidence we have it seems as if bilingualism continued for many generations. It is not impossible that a Norn/Scots Mixed Language emerged, which then gradually, but never fully, merged with Scots. We have evidence of mixed marriages from the time Scots speakers start settling on the islands, and contemporary testimonies mention how Shetlanders (“natives”) speak a ‘corrupt Norn’ among themselves. In other words, the typical social factors that have led to Mixed Languages elsewhere were also present in Shetland: long-drawn bilingualism, mixed marriages, and the potential threat to identity, as well evidence for the need of an in-group language. (Here I should stress that there is absolutely no evidence nor plausibility for any Creole language – as opposed to Mixed Language – emerging on the islands.) This might be similar to the situation with Michif (Canada), a Cree/French Mixed Language, which is now gradually merging with French, yet still retaining its distinctiveness.

English would gain more and more influence in Scotland with the Union of the Crowns in 1603. This would eventually spread to Shetland too. In 1709 the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge was established, and they set about establishing schools where the medium of instruction was English. By 1827 there was a school in every parish of Shetland, and with that the attitude that English was a more valuable language than Shaetlan was reinforced.

Shetland is now a bilingual community in English and Shaetlan, in that every Shaetlan speaker is bilingual in English. However, not every Shetlander speaks Shaetlan. The speaker numbers are difficult to assess; the 2011 census is misleading because it did not have Shaetlan as an option, only Scots and English, but many Shaetlan speakers do not identify themselves as speakers of Scots (‘we’re not Scottish, we’re Shetlanders’). A participant observer estimate would be that Shaetlan is probably spoken by about 30-50% of the population. The language is endangered in that transmission is declining. There are even activists working to promote Shaetlan who opt to speak English to their own children. It has never been a medium of instruction in schools.

Shaetlan is not intelligible to speakers of Standard English. It is both phonologically, prosodically, grammatically and lexically distinct. Some examples of salient and still highly prolific features:

Phonology: Shaetlan has the front rounded vowels /y/ and /ø/. The interdentals /θ/ and /ð/ are /t/ and /d/ in nearly all environments.

Prosody: polar questions are formed with falling intonation, even if the clause structure is identical with statements – the context marks the question.

Grammar: there is a pronominal number/politeness distinction: du is the informal 2 singular, while you is the formal 2 singular as well as the general plural. There is a three-way remoteness distinction for demonstratives: dis (proximal) ~ yun (distal) ~ dat (remote). They are number invariant. There is grammatical gender, where concrete count nouns are referred to as he or she, irrespective of animacy, while abstract and mass nouns are referred to as it. There is an associative plural an dem. The perfect is universally formed with be, as in A’m had denner ‘I’ve had lunch’. There is a pragmatically marked copula, come tae be X, which flags new and unexpected information. The relative marker is an invariant form (at).

Lexicon: a number of Norn derived lexical items remain in the language (nev ‘fist’, host ‘cough’, smit ‘infect’, etc.), as well as contact induced vocabulary, especially from the Low Germanic languages (proil ‘stuff’, dukkie ‘doll’, etc.). There are a number of false friends with English, such as denner ‘lunch’, fool ‘bird’, doot ‘believe’, seem ‘notice’, silly ‘sickly’, luck ‘entice’, messages ‘groceries’, learn ‘teach’, starvin ‘very cold’ etc.

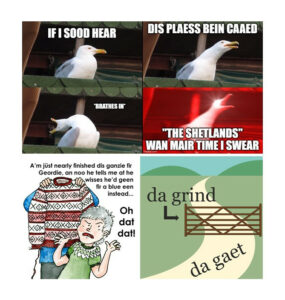

The Shaetlan Language Project aims to document and describe Shaetlan from a typological perspective. We have also devised an orthography and for the first time ever secured a place for Shaetlan in a mobile keyboard language list, which means that speakers for the first time ever have access to Shaetlan autocorrect and predictive text. We have gone online as I Hear Dee (a slightly tongue in cheek expression in Shaetlan), and on social media we regularly post bilingual bite sized snippets about the language, including culture notes. For example, it is never “the Shetlands” and we all live in Shetland (never “on”!). For more information about Shaetlan, the project and I Hear Dee, see https://www.iheardee.com/ .

Additional links:

Instagram: @iheardee

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/iheardee

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJSUqRqg8ACFo0LL38X51cA (until we can change it to something more meaningful)

Viveka Velupillai is Honorary Professor at the Department of English at the University of Giessen, Germany, but is based in Shetland. She specialises in linguistic typology, contact linguistics and historical linguistics, and her main project is to document and describe Shaetlan, the high-contact language spoken on the islands alongside English.

Absolutely fascinating, thank you for sharing the incredible history and language of Shaetlan with us!

Shetland News today:

https://www.shetnews.co.uk/2022/02/15/have-you-done-todays-wirdle-popular-word-game-given-shaetlan-slant/